The Golden Age of the West

The golden age of the West manifested in the glorious civilisation of al-Andalus–Islamic Spain, between 711 and 1492 AD. It embodied the pinnacle of civilisational splendour, intellectual ingenuity, philosophical myriads, scientific breakthroughs, cultural richness, artistic genius and architectural marvels. Western Muslims called it the Iberian Peninsula or Islamic Spain–Jazirat al-Andalus. Al-Andalus was ruled by various Muslim dynasties: the Umayyad State of Qurtuba or Cordoba 756-1031 AD, the First Taifa 1009-1110 AD, al-Murabitun or Almoravid 1085-1145 AD, Second Taifa 1140-1203 AD, al-Muwwahidun or Almohad 1147-1238, Third Taifa 1232-1287, and the Emirate of Gharnata or Granada 1232-1492 AD. Almost 800 years of the Andalusian period witnessed the heights of civilisation and ingenuity.[1] This article deals with the intellectual, philosophical, scientific, artistic, architectural and cultural contributions of al-Andalus. It asserts that al-Andalusia represents the golden age of the West and was foundational in setting the stage for the Renaissance and the Enlightenment in Europe. At the same time, Al-Andalus represents a unique period of intellectual flourishing from the perspective of Muslim civilisation. While Al-Andalus left an impression on the Europeans, it holds an integral place in the history of intellectual, philosophical, scientific, cultural, artistic and architectural advancements of the Muslim world.[2] Al-Andalus became the epicentre for intellectuals from across the east and west. Al-Andalus produced 11,831 scholars from various disciplines, with over 13,750 academic works between the 8th and 15th centuries. Al-Andalus was a magnificent representation of the Renaissance in the Muslim world.[3]

History of al-Andalus

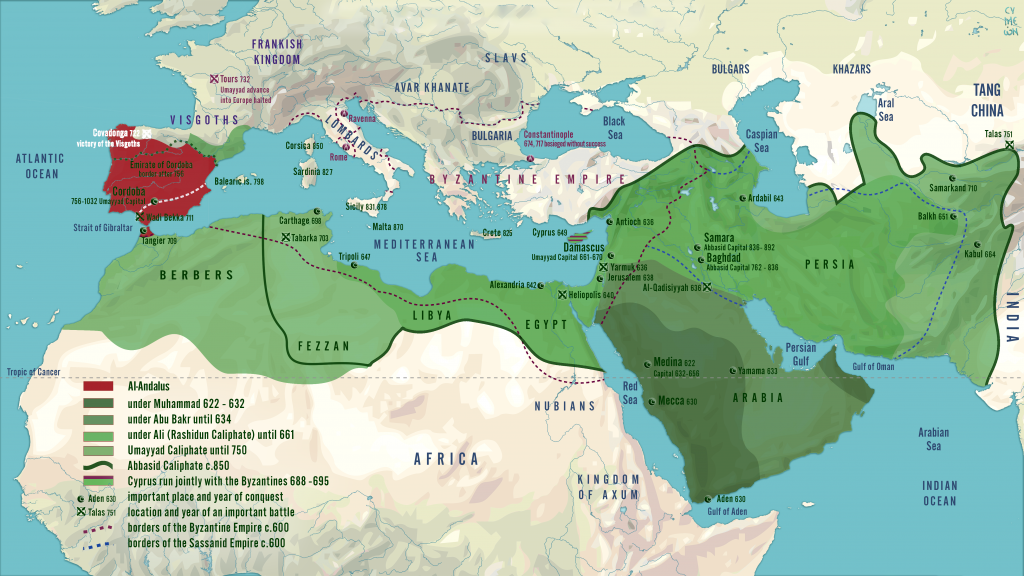

The mighty Roman Empire once held the Iberian Peninsula, the farthest limit of its rule. The Germanic Visigoths sacked the Roman province in 410 AD under the command of King Alaric. The Visigoths practised Arianism yet ruled a population which was Catholic in delineation. The Visigoths converted to Catholicism in 598 AD to legitimise their occupation. In the east, by 610 AD, the Arabian Peninsula had witnessed the beginning of the Prophetic mission. The beginning of the period of the righteously guided caliphs in 632 AD culminated with the rise of the Umayyad Dynasty in 661 AD. By 747 AD, the ‘Abbasids entered a conflict for power with the Umayyads and subdued most Umayyad princes with one exception. ‘Abd al-Rahman bin Mu’awiya (B. 731-788 AD and ruled 756-788 AD), the grandchild of Hisham bin ‘Abd al-Malik, escaped the conflict and landed in al-Andalus. ‘Abd al-Rahman bin Mu’awiya took power in al-Andalus and established the Umayyad State of Qurtuba in 756 AD.[4] Hisham bin Muhammad bin ‘Abd al-Malik III was the last Umayyad ruler of Qurtuba in 1031. The Umayyad Dynasty perished in the Eastern Muslim Empire in 750 AD but persisted in al-Andalus until the first quarter of the 11th century. The last surviving Umayyad prince, ‘Abd al-Rahman bin Mu’awiya, found refuge and established a glorious emirate in the west on the Iberian Peninsula. Al-Andalus has been attributed, therefore, to the Umayyad legacy.[5]

The Conquest of Andalusia

Ceuta is on Morocco’s edge and separated from Jabl al-Tariq—Gibraltar by the narrow strait. In 670 AD, General ‘Uqba bin Nafi’ took Northern Africa and established Qayrawan or Karaiouan, which inspired the modern-day word caravan. Musa bin Nusayr became governor of ‘Ifriqiyya—Northern Africa and Maghreb—the west in 698 AD. The original idea of the West stems from the Maghreb or the contemporary territorial region of Morocco, its surroundings, and eventually al-Andalus. Since al-Andalus was established by Muslims from Maghreb and other regions, al-Andalus became the first civilisation to be called the West. Andalusia represented the epitome of a Western civilisation.[6] It was the intellectual inheritor of ancient Greek heritage and gave the world innumerable breakthroughs in the realm of science, literature, medicine, philosophy, mathematics and architecture.[7]

Musa bin Nusayr imagined a great Muslim civilisation on the Iberian Peninsula. As someone who never saw defeat on the battlefield, Musa bin Nusayr was determined to establish dominion across the straits. It was held by the mighty Germanic Visigoths, who had uprooted the Byzantines. Despite numeric inferiority, Musa bin Nusayr was firmly convinced to emerge victorious. It would be a remarkable feat if Muslims were able to place a foothold on the European continent. To make this possible, Musa bin Nusayr mustered his most talented commander, Tariq bin Ziyad. An estimated twelve-thousand troops were mobilised, and Tariq bin Ziyad was ordered to sail across the Strait of Gibraltar and capture the Iberian Peninsula.[8]

The Germanic Visigoths stood mighty with an army of 100,000. As Tariq bin Ziyad sailed across the straits, he saw the Noble Messenger PBUH in his dream, wearing a sword on his belt, carrying a bow on his shoulder, walking upon the sea toward the Iberian Peninsula, commanding: “O Tariq, advance upon your course! Be good to the Muslims and loyal to your pledge!” (al-Maqarri, Nafh al-Tib). This dream compelled Tariq bin Ziyad to forget the unfavourable odds and convinced his victory was certain. Tariq bin Ziyad rose and hustled his compact force toward the insurmountable task of subduing the Visigoths and taking the Iberian Peninsula. Tariq bin Ziyad’s forces dismounted on the Iberian Peninsula, and the location was henceforward known as Jabl al-Tariq—the Rock of Tariq or Gibraltar.[9]

On the battlefield,~7,000 [1] Muslims standing against King Roderic’s 100,000 troops seemed an impossible task. However, Tariq bin Ziyad made a fateful decision which changed the course of the conflict. Tariq bin Ziyad commanded his forces to burn all the ships and vessels that had brought his army across the strait. Tariq bin Ziyad wanted his numerically smaller forces to have no doubt there was no going back, and the only way forward was by defeating Roderic’s 100,000-strong army. The Muslims were motivated and purposefully marched, whereas the Germanic Visigoths had no reason to fight. The Visigoths were sceptical about King Roderic and, therefore, had low morale. Despite the numeric inferiority, Tariq bin Ziyad’s forces had the moral advantage. During the battle itself, Tariq bin Ziyad masterfully used higher ground to mitigate his numeric inferiority and deflected the advances of the Visigoths.[10]

Three days of fighting ensued between the Muslims and the Visigoths. Tariq Bin Ziyad delivered a blistering motivational speech to his forces: “Whither can you fly—the enemy is in your front, the sea at your back? By Allah! There is no salvation for you but in your courage and perseverance!”. Eventually, the Muslim forces overwhelmed the Visigoths, and Roderic fled the battlefield. Roderic was trampled under his own forces while attempting to flee. Tariq bin Ziyad had achieved an unimaginable victory that paved the way for the conquest of Spain. Tariq bin Ziyad’s forces soon captured major cities in the peninsula, from Qurtuba—Cordoba, Elvira (Gharnata—Granada) and Malaqqa—Malaga. Tariq bin Ziyad’s forces defeated the Germanic Visigoths in August 711 AD, which marked the beginning of al-Andalus—Islamic Spain.[11]

Ahmad ibn Muhammad al-Maqqari al-Tilmisani (1577-1631 AD) was a great Andalusian historian from Tilmisan—Tlemcen, who wrote about the Muslim conquest of al-Andalus in his compendium on Andalusian history Nafh al-Tib:

وقال الوزير لسان الدين بن الخطيب – رحمه الله تعالى – في بعض كلامٍ له أجرى فيه ذكر البلاد الأندلسية،

أعادها الله تعالى للإسلام ببركة المصطفى عليه من الله أفضل الصلاة وأزكى السلام

The vizier Lisan al-Din al-Khatib said about the conquest of Andalusia by Muslims in 711 AD that “Allah swt returned Andalusia back to Islam by the blessings of al-Mustafa PBUH”. The Andalusians knew they had been gifted the Iberian Peninsula through the intermediation of the Prophet PBUH. Such was the certainty of their conviction in the Prophetic blessing.[12] Governor Musa ibn Nusayr arrived in Andalusia in 712 AD with a further contingent of 18,000 forces made up primarily of the nobility of Arab tribes. Musa ibn Nusayr brought a companion of the Prophet PBUH, al-Mundhir RA and 20 tabi’un (successors) alongside him. Many pious people, scholars, intellectuals, merchants, administrators, preachers and prominent Muslims migrated to al-Andalus early on. The foundation of Islamic Spain was based on knowledge and enlightenment. Its tenants rested upon the advancement of ‘ilm (knowledge), ‘aql (reason), intellect, science, philosophy, culture, architectural and artistic expression. From the outset, Andalusia became a civilisation that heralded exceptionalism and ingenuity.[13]

Umayyad Legacy in Andalusia

Following the fall of the Umayyad Empire and the rise of the ‘Abbasid Empire in the Muslim mainland, ‘Abd al-Rahman bin Mu’awiya assumed power in Andalusia in 756 AD. The Umayyad prince wanted to compete with the intellectual, scientific, literary, cultural and philosophical prowess of the ‘Abbasid Empire. The royal court was built upon this intellectual imperative. ‘Abd al-Rahman I needed a central establishment to house these intellectual endeavours, so he began constructing the Great Mosque of Qurtuba (Cordoba). Unique artistic and architectural elements from Damascus, Marrakesh and Iberia inspired the design. The remarkable Great Mosque of Qurtuba is still a wonderful piece of architecture.[14] Muhammad Iqbal praised the Great Mosque of Qurtuba in 1932: “Makkah of the cultured ones! Glory of the faith, that’s true! Through you, al-Andalus’ land has become as sacred as you. If underneath the sky there is beauty equal to yours, Nowhere will it be found but in the heart of the Muslim soul. Sacred precinct of Qurtubah! In passion, you were devised, Love that ever defies the laws of fading and demise. Your beauty and your majesty are witness to the man of God Beautiful and majestic is He, and in that, so you are”.

The Umayyads in Andalusia became the patrons of Sunni Islam. In the words of an Andalusian poet: “In the West, the sun of a caliphate has risen which is to shine bright with splendour in the two Easts”. Andalusia became a centre for theological, jurisprudential, mystical, philosophical and scholarly production for Sunni orthodoxy. The Umayyads in al-Andalus holstered the intellectual paradigm upon the path of ‘al-din al-hanif (the moderate path of religion). A famous court historian, Abu Bakr Ahmad ibn Muhammad ibn Musa al-Razi al-Kinani (888-955 AD), describes the Umayyad rulers in al-Andalus as having the maslaha—public interest in mind when devising policies. Al-Andalus was governed by the principle of public welfare and its inhabitants’ betterment, including Christians, Jews, and Muslims.[15]

Pluralism in Andalusia

Al-Andalus was a centre for multifaith exchange, dialogue and minority protection. Christians, Jews and Muslims alike practised their faith and ways with freedom. Despite the border skirmishes in north Spain with the Christian kingdoms, Muslim rulers in Andalusia guaranteed protection for their Christian subjects. The Umayyad rulers in Andalusia offered patronage to the Maliki fiqh but allowed open practice for the three other schools of jurisprudence. Emir al-Hakam I (796-822 AD) declared the Maliki fiqh a state delineation. However, various institutions and scholars openly taught and practised al-Fiqh al-Shafi’, al-Fiqh al-Hanafi and other sub-schools, including Zahirism. For example, the great Andalusian Ibn Hazm (d. 1064 AD,) who will be discussed in more detail later on, practised al-Fiqh al-Shafi’ for a while, as well as another eminent scholar Baqi ibn al-Makhallad (d. 889). There was some censorship in the ‘Abbasid Empire on the dissemination and practice of certain schools. However, in al-Andalus, there was pluralism, freedom to practise religion, a school of thought in Islam, and sub-schools and interpretations within religion.[16]

Andalusian Golden Age of Intellectual, Scientific, Philosophical and Scholarly Contribution

Andalusia became the centre of Western civilisation. Qurtuba became home to intellectual, economic, scientific, philosophical and artistic advancements across the Mediterranean, European and Muslim world. Ibn Sa’id al-Andalusi (1029-1070 AD) writes in Tabaqat al-Umam that before the Muslims arrived in the Iberian Peninsula, it was empty of science, philosophy and academic investigation. Ibn Sa’id was a qadi—judge in Tulaytilia—Toledo, and he compiled works on the history of philosophy, science and thought. Ibn Sa’id wrote Tabaqat al-Umam (Categories of Nations) in 1068, describing the scientific achievements of the Muslims-Arabs, Indians, Persians, Chaldeans, Egyptians, Greeks, Byzantines and Jews. Ibn Sa’id emphasised the contributions of Muslims to philosophy. Ibn Sa’id wrote about logic, Ptolemaic astronomy, logic, and trigonometry. Andalusian literature was carried to the Mediterranean and European kingdoms, becoming the precursor to the Renaissance and Enlightenment.[17]

Al-Hakam II—the Patron of the Golden Age

The rule of Emir ‘Abd al-Rahman al-Nasir li Din Allah III (912-961) and his son Emir Al-Hakam II (961-976) represent the golden age of Andalusia. ‘Abd al-Rahman III and al-Hakam II oversaw a period of intellectual, scientific, philosophical, artistic and architectural magnificence. The Andalusian state was in a dire situation before ‘Abd al-Rahman III came into power. It was a stagnant economy, an underperforming administrative unit and an unproductive intellectual era. ‘Abd al-Rahman III came to power and reversed this sluggish situation, propelling Andalusia to the heights of civilisational progress. ‘Abd al-Rahman’s III achievements culminated in the construction of Madinat al-Zahra in Qurtuba in the 10th century. It was a grand royal palace with Andalusian architectural prowess, beautiful gardens, fountains and various sections dedicated to crafts, intellectualism, artisanry and governance. ‘Abd al-Rahman III wanted to demonstrate the exceptionalism of Andalusia to rival courts in Ifriqiya (Africa), the Fatimid and the ‘Abbasid. Madinat al-Zahra means The City of Flowers or The Radiant City, but ‘Abd al-Rahman III inwardly attributed its name to the Prophet’s PBUH daughter, Fatima al-Zahra.[18]

‘Abd al-Rahman’s III son, al-Hakam II, inspired an epoch of intellectual renaissance in Andalusia. Just like his father ‘Abd al-Rahman III, who was highly prudent, knowledgeable and cultured, al-Hakam II demonstrated a talent for ingenuity from a very young age. Al-Hakam II was studied by the most notable scientists, intellectuals, philosophers, and scholars of al-Andalus. Al-Hakam II was a scrupulous reader from a tender age and enjoyed collecting books from distant lands. When al-Hakam II began his reign (961-976), he collected all the books and manuscripts he could from Cairo, Baghdad, and Damascus to be placed in his vast collection in Madinat al-Zahra and other royal libraries. Al-Hakam II is similar to the philosopher-king in Plato’s ethos and was considered a scholarly emir. Al-Hakam was the patron of scholarship, academia, research, scientific progress, philosophising, arts and architectural development. Al-Hakam II’s only wish was to take al-Andalus to the peak of civilisation.[19]

Al-Hakam II expanded Madinat al-Zahra into a city of knowledge and intellectual enterprise. The vast library held approximately 1 million books[2] [3] and manuscripts, including 44 volumes of the catalogue. To make al-Andalus the epicentre of philosophy, sciences, and intellectualism, al-Hakam II employed thousands of scholars, calligraphers, transcribers, bookbinders, summarises, researchers, scientists, and academics from all across the Muslim world. Al-Hakam’s II library in Madinat al-Zahra contained all humanity’s accumulated knowledge until then.[20]

Al-Hakam II commanded his scholars, scientists and researchers to carry the mantle of knowledge forward into the future. Al-Hakam II even wanted to outperform the endeavours of the Byzantine Romans. Madinat al-Zahra’s research centres were commanded to gather all Greek works and translate them into Arabic. This was an enormous endeavour in itself, as the Greek period had amassed powerful works ranging from mythology to philosophy. Al-Hakam II personally read and consumed everything his researchers were translating and oversaw the process of translating Greek works into Arabic. Al-Hakam II then commanded the Greek works to be translated into Persian, Hebrew, Latin, and regional dialects so that scholars of various linguistic and semantic differences could also read them.[21]

Al-Hakam II was a polymath himself—a specialist in various disciplines. Many scholars and writers would even send their works before publication to Emir al-Hakam II for review. Abu-l-Faraj (897-867 AD) would often send his poetry divan to al-Hakam II to read before he would publish. The Maliki jurist Abu Bakr al-Ahbari would also send his legal manuscripts to al-Hakam II to review before publishing. It was and is still today, unusual for scholars to send their academic works to heads of state for revision. Most heads of state are not well-versed enough to understand the intricate sensibilities of various disciplines, let alone offer peer review.[22]

The classical Islamic sciences, including usul al-fiqh (jurisprudence), usul al-hadith (hadith sciences), usul al-kalam (theology) and tarikh (history), were also supported by al-Hakam II. Al-Hakam II, for example, ordered the scholar Abu ‘Abbas Ahmad ibn Muhammad ibn Mufarraj, also known as al-Nabati (1166-1239 AD), to write books on jurisprudence, theology, hadith and tafsir. Al-Hakam II commanded Ahmad ibn Mugith (d. 1067) to compile works on Arabic poetry and literature. Ibn Mughith’s divan collected all Umayyad poetry and recitals together. Similarly, Al-Hakam II commanded the Andalusian historian Muhammad ibn Yusuf al-Tarikhi to cover North Africa’s and al-Andalus’s topography. Al-Hakam also ordered the Iraqi linguist and grammarian Ismai’l al-Qali to produce a vast anthology of the Arabic language, which eventually became an encyclopaedia. At the same time, Al-Hakam II wanted the history of the Franks to be compiled, and his court historians completed this. Various disciplines were overseen by the emir himself, and his patronage allowed these sciences and intellectual fields to prosper in Andalusia.[23]

Medical Research

Al-Andalus became an abode of medical research output and procedural innovation. Al-Hakam II commanded his top medical professionals, led by Abu al-Qasim al-Zahrawi or Abulcasis (936-1013 AD), to work tirelessly to innovate and produce an updated medical discipline. Al-Zahrawi was perhaps the West’s most outstanding physician and surgeon in the Middle Ages. Al-Zahrawi compiled Kitab al-Tasrif, a 30-volume medical encyclopaedia, recording all existing medical knowledge to date and Al-Zahrawi’s medical advancements. Kitab al-Tasrif was translated into Latin and disseminated all over Europe, leaving a lasting impression on surgical techniques and medical procedures. Al-Zahrawi’s discoveries include ectopic pregnancies, caesarean deliveries, the causes of paralysis, techniques of amputations, cataract operations, cauterisation methods, stitching methods, refined surgical procedures, treatment of warts, the litigation of blood vessels, invention of new dental instruments and surgical devices.[24]

Al-Zahrawi also devised the field of war medicine as a distinct sub-speciality in general practice. Al-Zahrawi perfected the technique of removing foreign bodies and organisms. Al-Zahrawi offered great insight into bone tautology, orthopaedics, and pharmacology. The Andalusian medical professional al-Zahrawi also wrote about medical ethics and was concerned with fostering an equitable and transparent relationship between doctor and their patient. Al-Zahrawi wrote extensively about offering equal and accessible healthcare for everyone, laying the foundations for universal healthcare. Al-Zahrawi’s works were translated into Latin and spread around Europe and the East, inspiring medical advancements during the Renaissance period in Europe. Abu al-Qasim al-Zahrawi was the West’s greatest physician and medical researcher and left a soaring legacy in medicine for centuries in Europe and the East.[25]

Diya’ al-Din Abu Muhammad ‘Abd Allah ibn Ahmad al-Malaqi (1197-1248 AD), known as Ibn al-Baytar, was another great medical expert and physician of Malaqqa or Malaga in Andalusia. Ibn Baytar compiled and recorded the entirety of Muslim contributions to the field of medicine, which included over 400 new medicines compared to the existing ones. Ibn Baytar was the student of the botanist Abu al-‘Abbas al-Nabati (1166-1239 AD). Ibn Baytar compiled Kitab al-Jami’ al-Mufradat al-Adawiyya wa al-Aghdhiyya (Compendium on Simple Medicine and Foods), which included over 1400 herbal plants, various foods and how to use them as remedies. It was a remarkable compendium of herbal medicine acknowledged widely around Europe and the East.[26]

Abu Marwan ‘Abd al-Malik ibn Zuhr (1094-1162) was a remarkable physician who produced five generations of doctors and medical experts in Andalusia. Ibn Zuhr was from Ishbiliyya and was a philosopher, medical expert, surgeon and poet. Ibn Zuhr was a rationalist medicinal expert who wrote his seminal work Al-Taysir fi al-Mudawat wa al-Tadbir (Book of Simplification Concerning Therapeutics and Diet), which was translated into European languages and spread around. Ibn Zuhr made surgical advancements as well, performing tracheotomies. Ibn Zuhr wrote Kital al-Iqtisad (The Book of Moderation), a treatise on psychology and mental health, for the al-Murabit prince Ibrahim Yusuf ibn Tashfin. It discussed various treatments for mental health issues, various therapeutic methods and general health-related remedies. Ibn Zuhr’s Kitab al-Taysir was a hefty book which provided new information on the diagnosis of diseases, describing remedies for stomach cancer and treatment for various bodily inflammations. Ibn Zuhr introduced medical and therapeutic experimentation on animals before trying them out on humans. Ibn Zuhr left a lasting impression on generations of medical experts to follow in Andalusia and Europe. Ibn Rushd (1126-1198 AD) was Ibn Zuhr’s contemporary and friend, regarding him as the greatest medical expert and physician since Galen. Ibn Zuhr’s daughters and granddaughters carried his legacy, becoming renowned physicians in Andalusia.[27]

A Welfare State

Al-Andalus developed into an equitable, egalitarian, welfare state that offered healthcare, education, trade, provisions, and shelter to all its inhabitants and migrants. Maslaha—public welfare is an antiquity principle of governance in Islam that Muslim rulers have almost forgotten today. Al-Andalus was governed by maslaha and public interest. Al-Hakam II established many government-run shelters, inns, and motels where the less fortunate and travellers could reside. At the same time, al-Hakam II established many hospitals, medical clinics and dispensaries for the sick and unwell, offering an early form of universal healthcare to all citizenry and foreigners of Andalusia.[28]

In Muslim countries today, infrastructure is built not for ordinary citizens or the public but to impress foreigners and draw tourism revenue. On the other hand, Al-Hakam II expanded the Great Mosque of Qurtuba not only to magnify Andalusia’s exceptionalism but also to offer locals and foreigners an opportunity to find solace and a place of networking. The mosque was not only a place of worship but also a place where researchers, scholars, students, merchants, travellers and common citizenry came to convene and liaison with each other. The Great Mosque of Cordoba was a public space everyone used for their ends—researchers, scholars and academics studied there. Merchants and traders concluded their deals at the mosque. Travellers and migrants found refuge, met with local guides and established contacts at the mosque.[29]

The Great Mosque of Qurtuba was a place of worship and for the common citizenry to socialise and network. This is one of the functions of a mosque that early Muslim societies offered, which has been shut down by zealots and Puritans today. The Great Mosque of Qurtuba was renovated by al-Hakam II with artistic mosaics, Kufic inscriptions, woodwork and ivory, as a testament to the glory of Andalusia but also to offer inhabitants and travellers a splendid place to frequent. Andalusia was developed into a flourishing urban space with courtyards, gardens, water fountains, covered markets, bazars, cafes, restaurants, public galleries, hospitals, educational institutes and administrative offices. Al-Andalus remains a hallmark civilisation in the West.[30]

Classical Scholarship, Philosophy, Science and Mysticism in al-Andalus

The Great Andalusian Polymath Ibn Hazm

Al-Andalus became a rival to the golden age of the ‘Abbasid dynasty in intellectual, philosophical and scientific endeavours. Scholars were encouraged to settle in Andalusia and engage in academia and research. Andalusia produced a legacy of intellectuals, philosophers, scientists, classical scholars, mystics and artists. Some of the most notable ones will be mentioned. Perhaps the most well-rounded Andalusian polymath was ‘Ali ibn Ahmad ibn Sa’id ibn Hazm (994-1064 AD), a classical scholar, traditionist, jurist, philosopher, theologian and historian. Ibn Hazm wrote 400 books on various disciplines. Ibn Hazm hailed from Qurtuba and was of Persian descent and some Spanish descent, which traces back to Ishbiliyya (Seville). Ibn Hazm emerged from a family of intellectual giants, as his grandfather Sai’d. His father, Ahmad, was a notable scholar in the royal courts of Emir Abu Amir Muhammad ibn ‘Abdullah Abi ‘Amir al-Ma’afiri, also known as al-Mansur (931-1002 AD), and his son Emir’Abd al-Malik al-Muzaffar also known as Sayf al-Dawla (975-1008 AD). Like many great scholars, Ibn Hazm was a third-generation intellectual. Ibn Hazm was trained in the Maliki school, yet he also studied al-Fiqh al-Hanafi and al-Fiqh al-Shafi’.[31]

Ibn Hazm was well-regarded in the Andalusian royal court and held several administration positions. Ibn Hazm served as Chief Minister in Qurtuba for a while in 1023. Ibn Hazm eventually left administrative posts and was taken into custody by officials at the behest of rival scholars. Ibn Hazm’s works were nearly as numerous as Ibn Jarir al-Tabari (839-923 AD) and Imam Jalal al-Din al-Suyuti (1445-1505 AD). However, due to political challenges and scholarly dissension, most of Ibn Hazm’s works were burned in Ishbiliyya (Seville). Of the 400 works or so Ibn Hazm compiled, approximately 40 works survive. Ibn Hazm wrote Tauq al-Hamama—The Ring of Dove, a poetic collection in 1022 reflecting on Platonic views and the importance of purity, restraint, piety, chastity and devotion for Muslims.[32]

Al-Fisal fi al-Milal wa-l-Nihal was a seminal work of Ibn Hazm which dealt with reason and revelation. It was on theology, the question of subjective perception, the shortcomings of ‘aql (reason), and the bargain between ‘aql (reason) and naql (transmission). Ibn Hazm argued for empiricism, data collection and factual enquiry over unrestrained reason. Ibn Hazm also wrote al-Mahalla bi al-‘Athar The Adjourned Treatise), which dealt with jurisprudence and creed. Ibn Hazm favoured a heavier leaning on the verses of the Qur’an, Prophetic traditions, and ijma’ (consensus) over qiyas (analogical reasoning). As a result of this discussion in al-Mahalla, Ibn Hazm has been categorised as a Zahiri (one who considers the apparent meaning of Quranic and Prophetic text over analogical reasoning). Dawud al-Isbahani (868-909 AD) was the founder of Zahiriyya and influenced Ibn Hazm’s delineation. However, Ibn Hazm never rejected qiyas or reasoning. Instead, Ibn Hazm was an empiricist who believed in building juristic and theological cases heavily upon data from Quranic and Prophetic text over an ‘aql (reason) heavy case. Ibn Hazm was, in essence, just arguing for a heavier emphasis on naql (transmission) over ‘aql (reason) and the superiority of the Quran and Sunna over analogy, rather than outright refuting ‘aql (reason) as is often thought. Ibn Hazm profoundly affected Andalusian tradition and died in western Seville in 1064. Ibn Hazm’s empiricism, Zahiriyya, and intellectualisation inspired generations of scholars in Andalusia.[33]

Bukhari of the West

Yusuf ibn ‘Abd Allah ibn Muhammad ibn ‘Abd al-Barr al-Qurtubi al-Maliki (978-1071 AD) was another great 11th-century Andalusian scholar and Qadi (judge) of Lishbuna or Lisbon in modern-day Portugal. Ibn ‘Abd al-Barr was considered the “Bukhari of the West” as he was a traditionalist of great stature. Ibn ‘Abd al-Barr wrote a book called Jami’ Bayan al-‘Ilm wa Fadlihi (The Exposition and Excellence of Knowledge), which was among the earliest compilations on the virtues of knowledge in the light of Prophetic traditions and the views of the pious predecessors. It remains a central work on the gravity of ‘ilm in classical Islamic literature. Ibn ‘Abd al-Barr compiled traditions and the history of the Prophet PBUH, the companions, and Prophetic campaigns. Ibn ‘Abd al-Barr is regarded as a towering figure in classical scholarship and a landmark scholar from Andalusia.[34]

Ibn Humayd al-Sabuni

Abu ‘Abd Allah Muhammad ibn Abi Nasr Futuh ibn ‘Abd Allah ibn Futuh ibn Humayd ibn Yasil (1029-1095 AD), who is known as ibn Humayd al-Sabuni, was another great Andalusian classicist. Originally from Azd, Yemen, al-Humaydi relocated to Mayurqa or Majorca. Al-Humaydi was a student of Ibn ‘Abd al-Barr and a contemporary of Ibn Hazm. The later portion of his life was spent in Mecca and Baghdad, which was dedicated to classical hadith sciences. Ibn Humaydi compiled Jadhwat al-Muqtabis fi Tarikh ‘Ulama al-Andalus—a history of the most notable scholars of Andalusia, which al-Humaydi wrote in Baghdad entirely from memory, without the help of his manuscripts. Ibn Humaydi also wrote his important Al-Jam’ bayn al-Sahihayn (the Compilation of the Sahih of al-Bukhari and al-Muslim), which is highly regarded in classical literature.[35]

Qadi ‘Iyad

Another great Andalusian classical scholar was Abu al-Fadl ‘Iyad ibn Musa ibn ‘Iyad ibn ‘Amr ibn Musa ibn ‘Iyad ibn Muhammad ibn ‘Abd Allah ibn Musa ibn ‘Iyad al-Yahsubi al-Sabti (1083-1149 AD) also known as Qadi ‘Iyad. He was a classical scholar who wrote extensively throughout his scholarly career on various disciplines, including theology, jurisprudence, exegesis, history, and genealogy. Qadi ‘Iyad was born in Sabta—Ceuta and lived in Andalusia during the al-Murabitun (Almoravid) period. Qadi ‘Iyad studied in Qurtuba and became a Qadi—judge in Sabta, Gharnata (Granada) and later in Qurtuba in 1137 AD. Qadi ‘Iyad eventually settled in Marrakesh, where he died in 1149 AD. Qadi ‘Iyad was among the most significant traditionalist scholars of the West. Qadi ‘Iyad’s most important work, al-Shifa’ bi ta’rif huquq il-Mustafa (Healing by the Recognition of the Rights of the Chosen One), is among the most foundational works on sira (genealogy and history) and fadail (rights and privileges) of the Prophet PBUH. The title of this work illustrates the amplitude of his conviction in the elevated status of the Prophet PBUH. It was written in response to certain scholars who did not outwardly confess the rights and station of the Prophet PBUH. An erroneous view emerged among some scholars that the Qur’an was the only miracle of the Prophet PBUH. Qadi ‘Iyad wrote al-Shifa’ as a refutation to demonstrate the numerous miracles, rights, ranks, stations and privileges of the Prophet PBUH as stemming from his genealogy, his Quranic status, his Sunna, his blessings, his miraculous actions and life as a Prophet. It is one of the most comprehensive books on the attributes of the Prophet PBUH and is still recognised as a timeless classic.[36]

The Great Philosophers, Scientists, Astronomers and Mystics of Andalusia

Al-Andalus became a repository of philosophy and intellectualism under the al-Murabitun (Almoravid). Abu ‘Abd Allah Muhammad ibn ‘Abd Allah ibn Masarra ibn Najih al-Jabali (883-931 AD), known as Ibn Masarra, laid the foundation for philosophical and mystical tradition in Andalusia. Al-Jabali was his laqab (title) as he travelled through various mountainous terrains during his lifetime. Ibn Masarra was educated by his father, Muhammad ibn Waddah (d. 900) and Abu ‘Abd Allah Muhammad al-Khushani (d. 971). Ibn Masarra practised Maliki fiqh and became the student of Abu Sa’id ibn al-‘Arabi (not to be confused with al-Shaykh al-Akbar Muhyuddin ibn ‘Arabi, who Ibn Masarra later inspired). Abu Sa’id ibn al-‘Arabi was a student of the great mystic from Baghdad, Junayd Baghdadi. Ibn Masarra spent time in Baghdad in the company of Abu Said ibn al-‘Arabi and Ahmad ibn Salim al-Tustari from the Salimiyya tariqa. After completing his education, Ibn Masarra returned to Andalusia under the rule of ‘Abd al-Rahman III and retreated to the Sierra of Cordoba with his students, where he died in 931 AD.[37]

Ibn Masarra’s most crucial work was Risal al-‘Itibar (Epistle of Contemplation), which discusses mental health, contemplation, meditation, and reaching higher truths and rational peaks. Kitab Hawas al-Huruf (Book of Sensory Letters) discusses Ibn Masarra’s views of spiritual wayfaring, Kitab al-Tabyin, and Al-Muntaqa min Kalam Ahl al-Haq (A Selection from the Saying of the Pious Ones). Many of Ibn Masarra’s books and manuscripts have been lost. Ibn Masarra was wrongly attributed to the Mu’tazila (rationalists). Ibn Masarra was a mystic scholar who inspired a generation after him, including al-Shaykh al-Akbar Muhyuddin ibn ‘Arabi (1165-1240), who was the most remarkable mystical scholar and polymath of Andalusia. Ibn Masarra laid the intellectual foundation for later philosophers in Andalusia.[38]

Abu Bakr Muhammad ibn Yahya ibn al-Sa’igh al-Tujibi ibn Bajja (1086-1138 AD), known as Avempace, was a remarkable Andalusian polymath and scholar who wrote on philosophy, astronomy, physics, medicine, botany, music and poetry. Ibn Bajja was from Zaraquza or Saragossa and later lived in Ishbiliyya (Seville) and Gharnata (Granada). Ibn Bajja lived during the reign of the al-Murabitun and the governorship of Abu Bakr ‘Ali ibn Ibrahim al-Sahrawi, known as ibn Tifliwit, who developed an intellectual relationship with ibn Bajja according to ibn al-Khatib from Andalusia. Where Ibn Sina (Avicenna) dominated philosophy in the east, Ibn Bajja (Avempace) dominated the west. Ibn Bajja wrote Governance of the Solitary, Risalat al-Wada (Letter of Bidding Farewell), Risalat al-Ittisal al-‘Aql bi al-Insan (Letter of Union of the Intellect with Human Beings), Tadbir al-Mutawahhid (Management of the Solitary), Kitab al-Nafs (Book on the Soul), and Risala fi al-Ghaya al-Insaniyya (Treatise on the Objective of Human Beings). Ibn Bajja was a remarkable Aristotelian philosopher. Ibn Bajja’s intellectualism was based on retreat, solitude, inward introspection, and realising inner grief and melody, which manifested in his close connection with poetry and classical Andalusian music. Ibn Bajja’s philosophy ultimately sought to carry ‘aql toward the ghaya (end) of haqq (ultimate truth). Ibn Bajja believed the soul was on a mystic and truth-seeking journey back toward its origin. Ibn Bajja despised the vices of materialism and luxury, instead suggesting the soul needed seclusion to nourish.[39]

Ibn Bajja also made inroads in astronomy, speaking about the difference between epicycles and eccentric spheres in the galaxy. Ibn Bajja proposed certain advancements from Greek understandings of the Milky Way Galaxy. Ibn Bajja also theorised about the transit of Venus and Mercury. In physics, Ibn Bajja advanced a theory of motion based on resistance between one object and another, improving the existing Aristotelian theory of projectile motion. Ibn Bajja also wrote about botany in Kitab al-Nabat (The Book of Plants), where he theorised about two genders in plants based on his research of various fruits and plants. Many of Ibn Bajja’s ideas developed Aristotle’s suppositions, yet he demonstrated a high degree of original thinking.[40]

Al-Murabitun and Philosophers

The Al-Murabitun (Almoravid) rule (1050-1147 AD) witnessed a spur of philosophers and scientists. Abu Bakr bin ‘Abd al-Malik bin Muhammad Tufayl al-Qaysiyy al-Andalusi (1105-1185 AD), known as Ibn Tufayl, was one of the greatest polymaths of Andalusia. Ibn Tufayl was a scholar, philosopher, writer, theologian, physician, astronomer, and government official. Ibn Tufayl was born in Gharnata (Granada) and was taught by Ibn Bajja. Ibn Tufayl served as a vizier to the al-Murabit Emir Abu Ya’qub Yusuf (1135—1184 AD and rule: 1163-1184 AD) and was also his personal physician. Ibn Bajja and his student Ibn Tufayl were critics of Ptolemy and his works and spent some of their writings critiquing them.[41]

Ibn Tufayl wrote Hayy ibn Yaqzan (Alive Son of Awake), which was translated into European languages and disseminated. Hayy ibn Yaqzan dealt with the limits of human reason and the ability to approach ultimate truth, allegorised by the journey of a young boy raised by a gazelle, attempting to reach higher truths about existence and the universe through his ‘aql (reason). Ibn Tufayl inspired a generation of scholars which included: Nur al-Din al-Bitruji (D. 1204), ‘Abd al-Wahid al-Marrakushi (1185-1250 AD), Ahmad al-Maqqari (1577-1632 AD), Lisan al-Din ibn al-Khatub (1313-1374 AD), Muhyuddin ibn ‘Arabi (1165-1240 AD), Abu Muhammad ‘Abd al-Haq ibn Ghalib ‘Abd al-Rahman ibn ‘Atiyya (1088-1147 AD) and most famously Abu al-Walid Muhammad ibn Ahmad ibn Rushd (14 April 1126—11 December 1198) or Averroes.[42]

Ibn Tufayl’s Philosophus Autodidactus aimed to bridge ancient Greek and Hellenistic philosophy with classical Islamic theology—kalam. Ibn Tufayl wrote partially in response to Abu Hamid al-Ghazali (1058-1111 AD) but also as a testament to his conviction toward rationalism. Hayy ibn Yaqzan became an instant best-seller when it reached European shores in the 17th and 18th centuries. It was a seminal work contributing to the so-called scientific revolution and the Enlightenment in Europe. Ibn Tufayl’s ideas influenced Enlightenment philosophers Immanuel Kant, Thomas Hobbes, John Locke and Isaac Newton. Ibn Tufayl wrote Rajz Tawil fi al-Tibb (A Long Poem in Medical Science) on the diagnosis of various diseases and illnesses, and it was composed in Arabic poetry to compel non-medical specialists to read it as well. Ibn Tufayl wrote Risala fi al-Nafs (Treatise on the Soul) and many other manuscripts that have not been recovered until now, dealing with various disciplines.[43]

Nur al-Din ibn Ishaq al-Bitruji (D. 1204 AD), known as Alpetragius, was a notable Andalusian philosopher, astronomer, scholar and Qadi from al-Bitrawsh (Los Pedroches) near Qurtuba. Al-Bitruji was known for his astronomical advancements and theorisation on planetary cycles and motions. Al-Bitruji was the first to present concentric spheres in response to the Ptolemaic approach based upon geocentrism. Al-Bitruji wrote about the celestial systems and their physical causes. Al-Bitruji’s astronomical models were disseminated all around Europe for centuries to follow. Al-Bitruji wrote Kitab al-Hay’a (The Book of the Structure), which critiqued Ptolemys Almagest and Al-Bitruji’s work and was widely received in Europe for centuries after being translated into Latin in 1217 AD.[44]

‘Abd al-Haqq bin Sab’in al-Mursi 1216-1271 AD), known as ibn Sab’in, was another splendid mystic, philosopher and intellectual from al-Andalus who was from Mursiyya or Murcia. Ibn Sab’in was a Neoplatonist who worked to advance classical Greek philosophy. Ibn Sab’in most notably responded to the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II’s Sicilian Questions in his al-Kalam ‘ala al-Masail al-Siqliyya (Discourse on the Sicilian Questions). Emperor Frederick II had enquired Muslim philosophers about classic Greek philosophy and pertinent questions about existence. Ibn Sab’in wrote his Discourse on the question of the world’s eternity, creation, Aristotelian view, the perspectives of the mystics, the soul, the mind, intellect, divine knowledge, and rationalism. This masterpiece was widely disseminated in Europe and became a symbol of the transfer of Muslim enlightenment into the West.[45]

Two Andalusian Poles

The two greatest polymaths of Andalusia were ibn ‘Arabi and ibn Rushd (Averroes). Abu al-Walid Muhammad ibn Ahmad ibn Rushd (1126-1198 AD) was a philosopher, jurist, classical scholar, theologian, medicinal expert, astronomist, physicist, psychologist, mathematician, legal and linguistic expert. Ibn Rushd authored over 100 works during his lifetime, most notably commentaries on the works of Plato and Aristotle, which were carried to Europe and the rest of the West. Ibn Rushd was unconvinced by the neo-Platonic tradition of Muslim scholars such as al-Farabi and Ibn Sina (Avicenna), favouring Aristotelianism. Ibn Rushd was a proponent of falsafa (philosophy), arguing it had a place in classical Islamic literature. Ibn Rushd wrote Tahafut al-Tahafut (The Incoherence of the Incoherence) as an attempt to defend falsafa from Imam Abu Hamid Muhammad al-Ghazali’s (1058-1111 AD) critique of it in his masterpiece Tahafut al-Falasifa (The Incoherence of the Philosophers). Ibn Rushd strongly believed there was room for rational philosophising, even in classical literature. In contrast, it had been the view of al-Ghazali that the type of neo-Platonic and neo-Aristotelian philosophy that had spread in the Muslim world was eroding the originality and puritanism of classical theology and the essence of religious sciences.[46]

A Response to the Criticism of al-Ghazali’s Tahafut al-Falasifa

A certain few have mistakenly presumed al-Ghazali’s critique of falsafa marked the end of rationalism or empiricism in the Muslim academic landscape. Neil deGrasse Tyson has famously argued that al-Ghazali’s intervention resulted in a stagnation of rational intellectualism in the Muslim world. This view is limited and erroneous and unlikely to be formed from an improper reading of al-Ghazali’s Tahafut al-Falasifa in Arabic. Suppose al-Ghazali’s Tahafut al-Falasifa is actually read thoroughly. In that case, it is a masterfully written work illustrating the degree to which al-Ghazali had a firm grasp of the prevalent neo-Platonic, neo-Aristotelian rationalism. It was also a deep enough reading to pinpoint its shortcomings. Al-Ghazali was primarily concerned with the induction of neo-Platonic and neo-Aristotelian views in kalam (classical theology) in Islamic literature. In his treatise, Al-Ghazali critiqued the discrepancies and disparity of neo-Platonic and neo-Aristotelian views of Muslim philosophers. In Tahafut al-Falasifa, al-Ghazali, in the chapter on Madhab al-Falasifa (School of the Philosophers), examines the views of Muslim neo-Platonic and neo-Aristotelian philosophers and proceeds in a subsequent chapter to thoroughly critique and refute their views. Al-Ghazali had unearthed the weaknesses of neo-Platonism and neo-Aristotelianism, which enlightenment thinkers in Europe greatly appreciated many centuries later.[47]

Al-Ghazali most certainly did not put an end to rationalism, empiricism, intellectual advancement or scientific enquiry in the Muslim world. Al-Ghazali was specifically concerned with the induction of neo-Platonic and neo-Aristotelian perspectives in kalam (classical theology). Al-Ghazali disputed the philosophers’ take on eternity, existence or co-existence, creation or eternity of heaven, the attributes of Allah Almighty, and similar debates that had been convoluted by ancient Greek and Hellenistic philosophy. Al-Ghazali contended that these neo-Platonic and neo-Aristotelian frameworks created unnecessary myriads and complexities in kalam (classical theology). Al-Ghazali argued that the philosophers would say something and rebut themselves a few passages later. There was an intrinsic incoherence in their arguments and insufficient consistency in their rationale. Hence, al-Ghazali called his book Incoherence of the Philosophers. Al-Ghazali’s critique of ancient Greek philosophy was absorbed by the European philosophers, who took inspiration from al-Ghazali’s works and levelled criticism upon neo-Platonism and neo-Aristotelianism centuries later during the Enlightenment period. In reality, al-Ghazali was the first to point out the discrepancies and complexities of ancient Greek philosophy.[48]

Al-Ghazali himself was a polymath who wrote about logic, philosophy, and ‘aql (rationalism) and advanced his own views in these disciplines. To say he was anti-rationalism is inconclusive. Al-Ghazali wrote Maqasid al-Falasifa (Aims of the Philosophers), which detailed the most pertinent debates at the time in philosophy, where al-Ghazali expanded upon ibn Sina’s (Avicenna) ideas. Al-Ghazali wrote Tahafutal-Falasifa (Incoherence of the Philosophers), refuting the complexities of existing philosophy in the Muslim world. Al-Ghazali also wrote Mi’yar al-‘Ilm fi fan al-Mantiq (Criterion of Knowledge in the Art of Logic), which offered an account of debates in logic and his own perspectives on the field. Al-Ghazali wrote Mihak al-Nazar fi al-Mantiq (Touchstone of Reasoning in Logic) on the principles of logic. Al-Ghazali also advanced his own views on existing philosophical trends, arguing for a moderate and cautious approach in al-Qistas al-Mustaqim (The Correct Balance). Al-Ghazali was not the cause for the deterioration of rationalism, empiricism, scientific advancement, or intellectualism in the Muslim world, as a certain few have argued. In fact, al-Ghazali not only had a firm grasp of existing philosophical trends, logic, and rationalism, but he also contributed to literature in his own writings. The overall political and territorial chaos that ensued following the Mongol raid of Baghdad in 1258 and the subsequent division of intellectual centres into smaller cities and regions in the Muslim world is more likely the reason for the overall decline of intellectualism.[49]

Ibn Rushd—Averroes

Ibn Rushd, in his own right, was a splendid Andalusian philosopher and equally well-versed in classical Islamic sciences. Ibn Rushd specialised in hadith sciences, fiqh (jurisprudence), theology, science and medicine. Ibn Rushd studied Maliki fiqh under Abu Muhammad ibn Rizq. Ibn Rushd studied hadith sciences with Ibn Bashkuwal and even memorised al-Muwatta of Imam Malik from his father. Ibn Rushd studied medicine and philosophy from Abu Ja’far Jarim al-Tajail. Ibn Rushd was a contemporary of Ibn Tufayl and had read the works of Ibn Bajjah. Ibn Rushd was very well-versed in Greek literature and was once cross-examined by crown prince Abu Yusuf Ya’qub al-Mansur on the question of whether heaven was created or eternal. Ibn Rushd was a bit hesitant to unsheathe his intellectual sword, so Ibn Tufayl, who was also present in the royal court and more acquainted with the crown prince, started to speak openly about Plato and Aristotle. Eventually, Ibn Rushd broke out of his shell and divulged a sea of knowledge to the future Emir, leaving an invaluable impression on him. When Abu Yusuf Ya’qub became the Emir, he became an ardent supporter of Ibn Rushd and appointed him to the post of Qadi of Qurtuba and later of Marrakesh.[50]

Eventually, Ibn Rushd migrated to Marrakesh, where he spent his time performing astronomical experiments and doing scientific research. Ibn Rushd oversaw the establishment of educational institutes and colleges under the al-Muwwahidun (Almohad) rule in Marrakesh. Soon, Ibn Rushd moved to Ishbiliyya (Seville) and became the Qadi. It was in this period between 1169 and 1179 AD when Ibn Rushd wrote most of his works. Ibn Rushd wrote treatises on philosophy, syllogism, intellect, the motion of the sphere, al-Farabi’s logic, Aristotle’s logic, the metaphysics in ibn Sina’s works, Fasl al-Maqal (The Decisive Treatise) bridging classical Islamic sciences and philosophy, al-Kashf ‘an Manahif al-Adillah (Exposition of the Methods of Proof) and on his landmark Tahafut al-Tahafut in 1180 AD. Ibn Rushd was a prolific writer in many different disciplines, and his work became an instant hit when it reached European academic circles later on.[51]

At the same time, Ibn Rushd was an accomplished medical expert who served as the court physician of the al-Muwwahidun (Almohad). Ibn Rushd wrote extensively on medical science. Ibn Rushd’s most seminal work was al-Kulliyat al-Tibb (The General Principles of Medicine), which spread around Europe years later. Ibn Rushd also wrote a work called On Treacle: The Differences in Temperament and Medicinal Herbs, on common remedies for illnesses, where ibn Rushd detailed various new forms of remedies to common diseases and illnesses. On the other hand, Ibn Rushd was also a legal expert and wrote extensively on Islamic jurisprudence. Ibn Rushd wrote Bidayat al-Mujtahid wa Nihayat al-Muqtasid on the framework of a legal expert who employs independent reasoning to determine jurisprudential rulings as well as the differences in the four schools of thought in Islamic jurisprudence. Ibn Rushd had an enormous impact on the emergence of the Renaissance in medieval Europe. Ibn Rushd was considered the father of rationalism in Europe. Ibn Rushd’s commentaries and original contributions to the works of Aristotle were widely read and appreciated around Europe for many centuries.[52]

Al-Shaykh al-Akbar

Abu ‘Abd Allah Muhammad Ibn ‘Arabi al-Tai al-Hatifi al-Andalusi (1165-1240 AD), known as al-Shaykh al-Akbar Muhyuddin Ibn ‘Arabi was the greatest mystic, intellectual, classical scholar and thinker from al-Andalus. Ibn ‘Arabi was born in Mursiyya or Murcia into a royal Arab family from Tlemcen with wealth and privilege, which he gave up in the pursuit of sacred ‘ilm (knowledge) and the path of ma’rifa (gnosis). Ibn ‘Arabi’s father, ‘Ali ibn Muhammad, was an officer in the army of the governor of Murcia, Ibn Mardanish. Ibn Mardanish passed away when Murcia fell to the al-Muwahhidun in 1172 AD, and Ibn ‘Arabi’s father joined the court of Emir Abu Ya’qub Yusuf. Ibn ‘Arabi was a young boy when his family settled in Ishbiliyya (Seville). Al-Shaykh al-Akbar Ibn ‘Arabi studied under some of the most eminent scholars of his time, receiving ijaza (formal authorisation to transmit knowledge) from renowned scholars such as ‘Ali ibn al-Hasan ibn Hibat Allah ibn ‘Abd Allah Thiqat al-Din Abu al-Qasim ibn ‘Asakir (d. 1176), Abu Tahir al-Silafi (d. 1180), Khalaf ibn Bashkuwal (d. 1183), and ‘Abd al-Haq al-Ishbilli (d. 1185)—a student of Ibn Hazm, whose works Ibn ‘Arabi deeply engaged with and mastered. Ibn ‘Arabi was also the student of Aby Zayd al-Suhayli (D. 1185), Ibn Zarqun (D. 1190), Ibn al-Jadd (D. 1190) and Abu Madyan Shu’ayb ibn al-Husayn al-Ansari al-Andalusi(D. 1197) who was trained by Shaykh ‘Abd al-Qadir al-Jilani (D. 1176), making al-Shaykh al-Akbar ibn ‘Arabi a one removed student of Shaykh ‘Abd al-Qadir al-Jilani.

Ibn ‘Arabi also learned from the great polymath Ibn Rushd (D. 1198) various scientific, legal and philosophical disciplines. Ibn ‘Arabi studied under the great jurists Ibn al-Jawzi (D. 1201), Ibn Abi Jamra (D. 1202), Abu Shuja’ al-Isfahani (D. 1212), Jamal al-Din bin al-Harastani (D. 1217) and Ibn Malik (D.1274). Ibn ‘Arabi spent his first years studying with the most eminent scholars from across the Muslim world. During the course of his life, Ibn ‘Arabi absorbed a magnanimous compendium of sacred ‘ilm (knowledge) from the most established intellectuals, philosophers, mystics, scientists and scholars of the era.[53]

Al-Shaykh al-Akbar ibn ‘Arabi left to begin his classical education for Tunis, Ishbiliyya and Fez in 1193 AD when he was 28 years old. Al-Shaykh al-Akbar Ibn ‘Arabi, in his Risala al-Mubashirat, describes a vision he had when he was young and had not begun his educational journey. Ibn ‘Arabi says his colleagues were insisting he learned al-fiqh rather than hadith collections. At this moment, Ibn ‘Arabi had not initiated his learning of either. Ibn ‘Arabi says he then had a dream in which he was standing in a wide field, and he was being attacked by assailants with weapons from all around him. Ibn ‘Arabi then saw the Prophet PBUH standing on top of a hill, so he ran to find refuge with the Prophet PBUH. The Prophet PBUH embraced ibn ‘Arabi and offered him safety from the assailants. The Prophet PBUH said to ibn ‘Arabi: “O my son, stay close to me, you shall remain safe and peaceful”! Ibn ‘Arabi says that those assailants then vanished, and from that moment onwards, he started to consume the vast collections of hadith. Ibn ‘Arabi spent time under the mystical tutelage of Muhammad ibn Qasim al-Tamimi. In 1202 AD, Ibn ‘Arabi arrived for Hajj and remained there for 3 years, completing his seminal work al-Futuhat al-Makkiyya (The Meccan Illuminations). Ibn ‘Arabi then travelled throughout the Muslim world, from ‘Iraq, Palestine, Anatolia and eventually Damascus, where he settled and passed away in 1240 AD. In Damascus, Ibn ‘Arabi completed his final revision of al-Futuhat al-Makkiyya and his famous work Fusus al-Hikam (The Bezels of Wisdom). Al-Shaykh al-Akbar Ibn ‘Arabi was a prolific writer who penned approximately 850 works. Only a select few works of Ibn ‘Arabi remain, and the vast collection of work has been lost over time.[54]

Al-Shaykh al-Akbar Ibn ‘Arabi’s most prolific idea was al-Insan al-Kamil (The Perfect Man), which was a doctrine on the Prophet PBUH as a reflection of complete inner and outer fulfilment. Ibn ‘Arabi was referring to al-Haqiqa al-Muhammadiyya (the Reality of Prophet Muhammad PBUH) as the leader of all creation and a role model for everyone to emulate. Al-Shaykh al-Akbar ibn ‘Arabi also wrote about Wahdat al-Wujud (Unity of Being), which was an ancient Greek-inspired term suggesting everything reduces back to oneness, singleness or one origin. Ibn ‘Arabi pondered upon the meaning of the Qur’anic verse of al-Baqara: 156 قَالُوٓا۟ إِنَّا لِلَّهِ وَإِنَّآ إِلَيْهِ رَٰجِعُونَ, “Surely to Allah we belong and to Him we will all return,” and explained it through his own perspective. The concept of Wahdat al-Wujud represents Ibn ‘Arabi’s reflection of this Qur’anic verse, which suggests everything in existence shall return back to the One: Allah Almighty. This was the entirety of the concept of Wahdat al-Wujud (Unity of Being). Ibn ‘Arabi was misunderstood by a few who lacked an adequate grasp of the Arabic linguistics, semantics, as well as the mustalahat (terminologies) of tassawuf (Sufism), falsafa (philosophy) and kalam (classical theology) of that era. What Al-Shaykh al-Akbar ibn ‘Arabi actually presented was an explanation of a very traditional Qur’anic idea that everything in existence has been created and is from Allah Almighty and shall, therefore, return back to Allah Almighty. Those who have studied the works of al-Shaykh al-Akbar ibn ‘Arabi’s stepson and intellectual successor, Sadr al-Din al-Qunawi (1207-1274 AD), can grasp the matter with more clarity. Sadr al-Din al-Qunawi’s works demystify and expound upon the intellectually complex works of al-Shaykh al-Akbar. Sadr al-Din al-Qunawi is often considered a mandatory reading before attempting to unravel the magnificent works of ibn ‘Arabi. Al-Shaykh al-Akbar Muhyuddin ibn ‘Arabi was the most eminent mystic, intellectual, and classical scholar in Andalusian history.[55]

Poetry and Literature

Al-Andalus became a home for poets and literary writers who wished to compete with their counterparts from the ‘Abbasid dynasty. Abu al-Walid Ahmad ibn Zaydouni al-Makhzumi (1003-1071 AD) was from Qurtuba and was considered the most significant poet of Andalusia. The Emirs al-Mu’tadid (854-861 AD) and his son al-Mu’tamid (842-892 AD) were also capable poets, as well as Ibn ‘Ammar (1031-83 AD) and ibn Hamdid (1055-1132 AD). The Andalusian poets wrote about escapism into the beauty of nature. Seeking a pardon from the oblivion of existence, Andalusian poets embellished their writings with the beauty of the landscape, mountainous terrains, seas and vast deserts as a place of refuge.

Abu Bakr al-Turashi (1059-1139 AD), known as Ibn abi Randaqa, wrote Siraj al-Mulk (Light of the Kings) in praise of Andalusian court high culture and royal etiquette. This masterpiece was widely consumed around Europe centuries later. Abu al-Walid al-Himyari (1026-1084 AD) wrote about fine nature – the delicacy of flowers, spring and nature. Al-Shaqundi (D. 1231) wrote an epistle on Andalusian customs and culture. Whereas Badi’ al-Zaman al-Hamadhani (969-1008 AD) developed the maqama style, which was a new form of anecdotal poetry. Ibn ‘Abd Rabbih (860-940 AD) was another great Andalusian poet who wrote his famous poetic work called al-‘Iqd al-Farid (The Peerless Necklace), which became an instant hit in Andalusia and also Europe for centuries. Ibn ‘Abd Rabbih also wrote Urjuza, which was a classical qasida (ode) in commemoration of ‘Abd al-Rahman III’s exploits on the battlefield. Perhaps the most recognised poet of Andalusia was Muhammad ibn Hani’ al-Andalusi al-Azdi (936-973 AD), who was regarded as al-Mutanabbi’ of the west. Ibn Hani’ was born in Qurtuba, moved to Ishbiliyya, and eventually joined the Fatimid court under the rule of al-Mui’zz. Andalusian poets inspired the rhyme revolution in the 10th and 11th centuries, adding new metrics to Arabic poetry. The manometer and monorhyme qasida were added to poetry by Andalusian poets.[56]

Andalusian Music

Abu al-Hasan ‘Ali ibn Nafi’ Ziryab (789-857 AD) was from Baghdad but migrated to Qurtuba. Ziryab was a singer, composer, musician, poet, astronomer, artist, botanic expert, and classicist. Ziryab was invited by Al-Hakam I (who ruled between 796-822 AD) and his son, ‘Abd al-Rahman II, who offered patronage to Ziryab’s musical and artistic career. Ziryab invented new forms of classical Andalusian music, training a generation of musicians in Andalusia. Ziryab refined the oud instrument and added the fifth string to increase the range of notation, which Ziryab believed represented the tune of the soul.[57]

Architecture and Arts

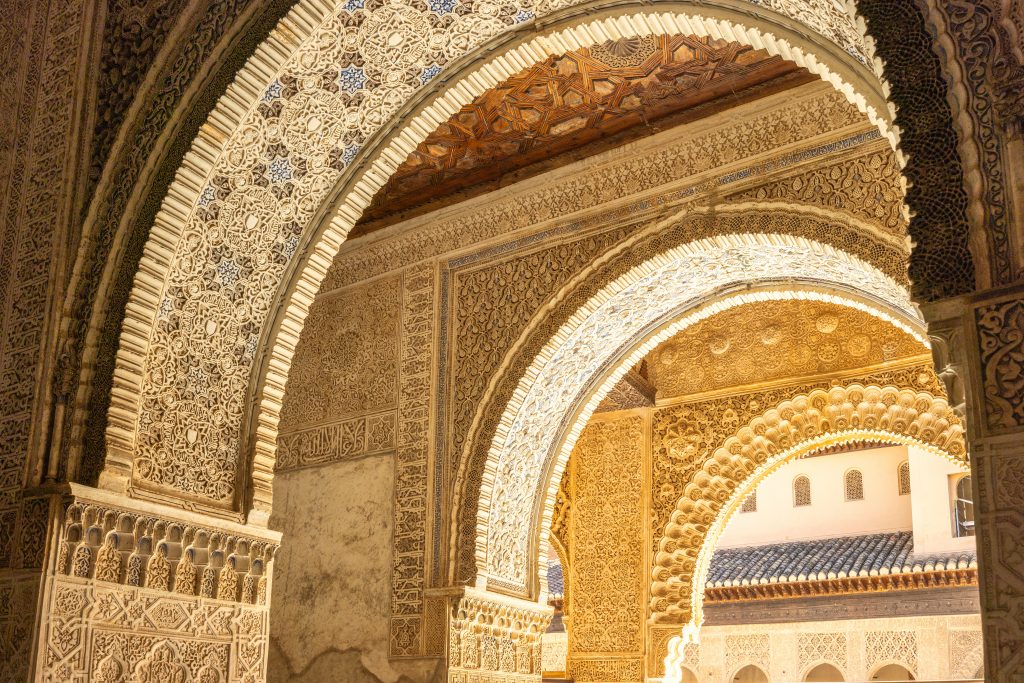

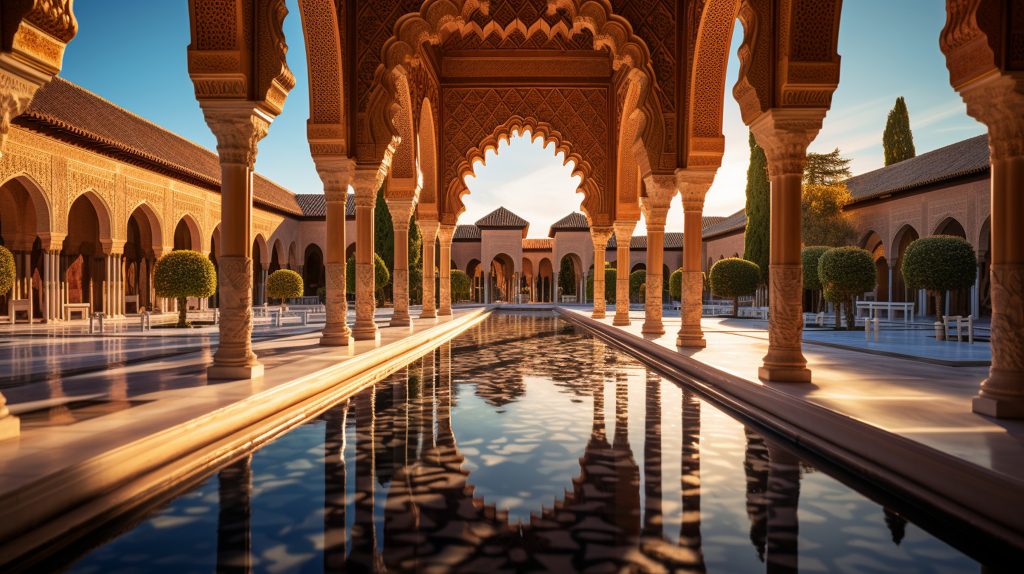

Andalusian architecture and design peaked in the 10th century when the Great Mosque of Qurtuba was completed by ‘Abd al-Rahman I and further expanded by ‘Abd al-Rahman II, al-Hakam II and al-Mansur. It was a representation of Andalusian artisanship, design language and heritage. From the intricate mosaic work to the arches and domes, Andalusian architecture left a lasting impression. The original blueprints of the Great Mosque of Qurtuba do not exist, but it is supposed that it was inspired by Umayyad design mixed with design elements from Ifriqqiyya and Iberian heritage. Madinat al-Zahra was also a splendour of architectural magnificence. It was, unfortunately, not preserved. Marvellous gardens, fountains, courtyards, palaces and design language can only be imagined, whereas the Great Mosque of Qurtuba was kept intact after the capture of Andalusia by the Catholics as they converted it into a cathedral.[58]

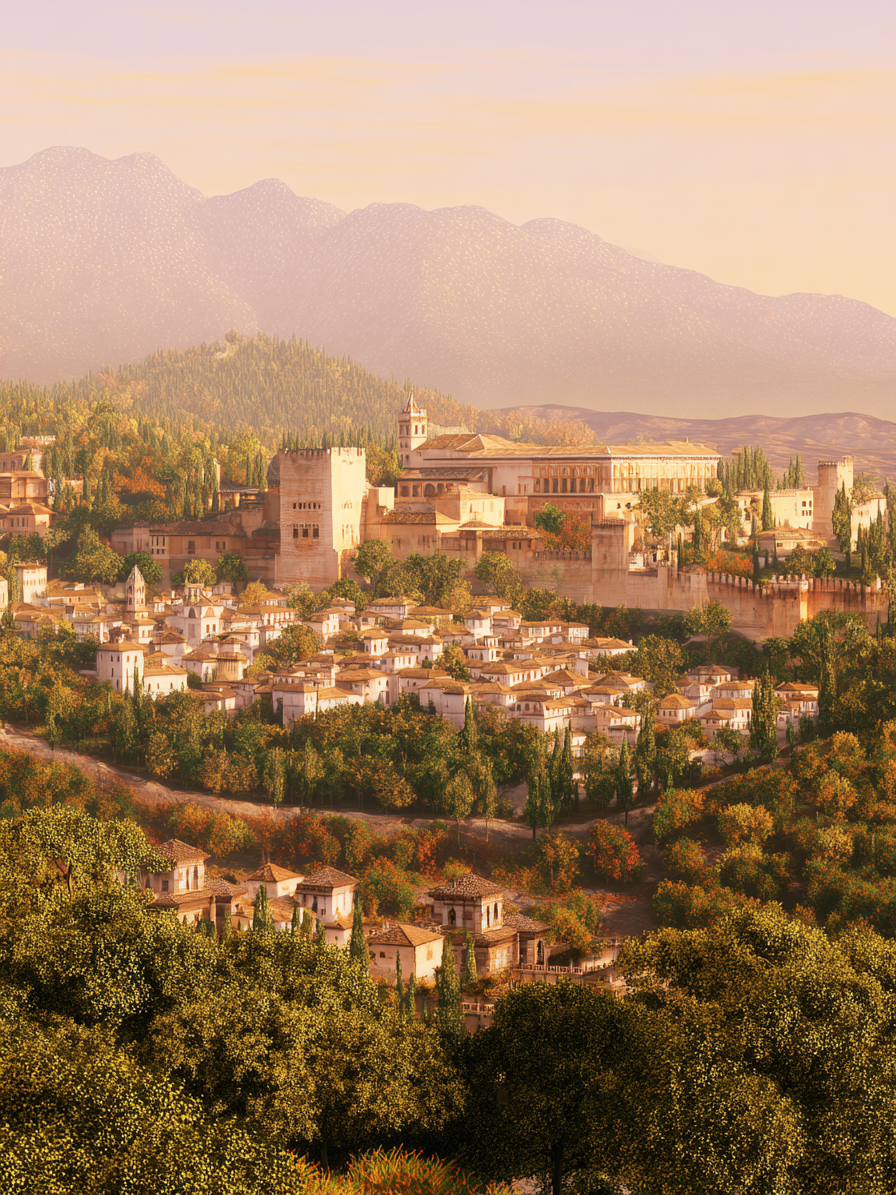

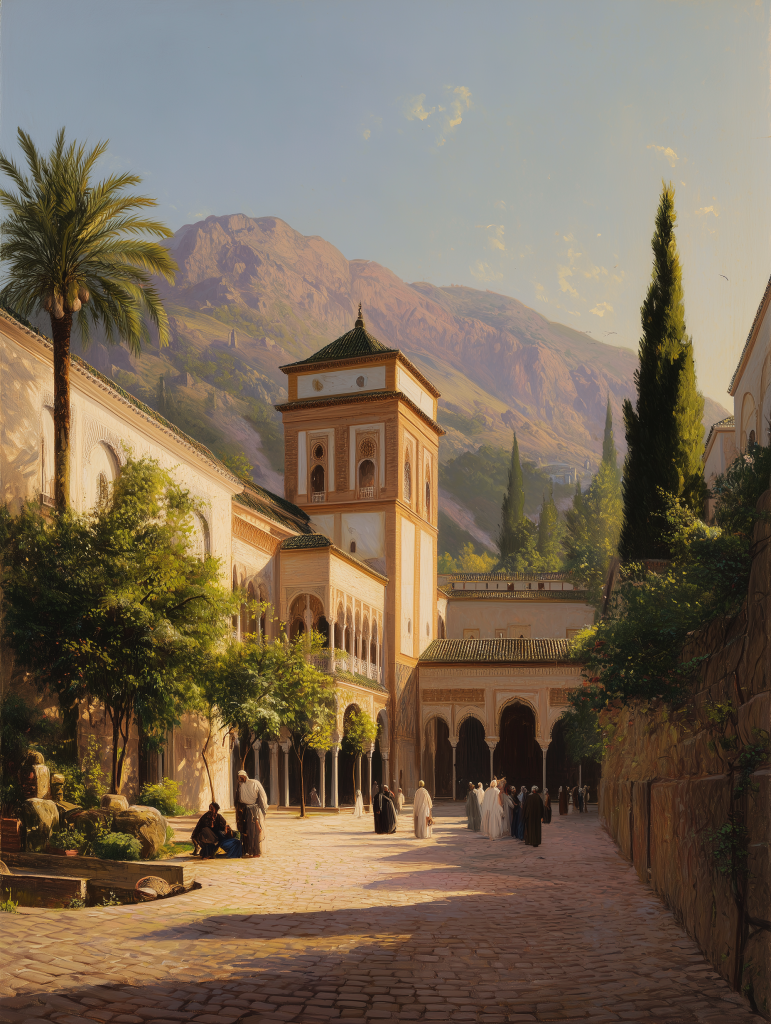

In Ishbiliyya or Seville, the al-Muwwahidun constructed a Great Mosque, which was also converted into a cathedral by the Catholics. Its large minaret is a famous tourist destination, and it is known as the Giralda. The Catholics converted this minaret into a bell tower. Al-Muwwahidun constructed the Alhambra Palace and the Palace of Gharnata (Granada), which illustrated the timeless design language of Andalusia. Alhambra was constructed by the first Nasrid Emir ibn al-Ahmad (1232-1273 AD) and then completed by Emir Yusuf (1333-1353 AD) and Emir Muhammad V (1353-1391 AD). Alhambra combined elements from Andalusia and Ifriqiyya. Alhambra’s courtyard was the central space filled with mosaics, water fountains, gardens, calligraphy, motifs, and designed ceilings. These timeless artistic elements were absorbed by Christian monarchies who carried them into European architecture. The Mozarabic art of the Kingdom of Leon and the Mudejar-style Church of San Roman in the city of Aragon reflected Andalusian design, as well as Alcazar of Seville, which was an al-Muwahhidun palace absorbed by Christian rulers. Andalusian architecture left a lasting legacy for the European Renaissance and kingdoms to follow.[59]

The Andalusian Sun Sets

In 1492, the Catholic kingdoms of Leon Castile captured al-Andalus. Catholics absorbed the vast intellectual collection of Andalusia and carried it into Europe, setting the foundation of the Renaissance and later Enlightenment. Andalusian scholarship and knowledge production were central to the European intellectual and cultural renaissance, which occurred as Andalusia fell. Ibn Rushd (Averroes) was celebrated as the founder of rationalism, al-Zahrawi as the founder of modern medicine and Ibn ‘Arabi as a towering figure in mysticism. Muslims were forcibly converted by Catholics, and by 1500 AD, the legacy of Andalusia had been desecrated. At its zenith, al-Andalus represented the pinnacle of intellectual, philosophical, scientific, medicinal, astronomical, artistic, classical, traditionist, architectural and civilisational magnificence and glory. Al-Andalus represented the highest point of Western civilisation centuries before the idea of the West even came into existence! Andalusia also held a unique place in the history of Muslim civilisation and in intellectual, philosophical, scientific, architectural and classical heritage.[60]

“When The Rain Cried Over al-Andalus” by Lisān al-Dīn Ibn al-Khaṭīb

جَادَكَ الغيْثُ إذا الغيْثُ هَمى

يا زَمانَ الوصْلِ بالأندَلُسِ

May the rain fall upon you in grace,

O time of union in Andalus’ place.لمْ يكُنْ وصْلُكَ إلاّ حُلُما

في الكَرَى أو خِلسَةَ المُخْتلِسِ

Your embrace was but a dream we chase,

Seen in sleep, or stolen in haste.إذْ يقودُ الدّهْرُ أشْتاتَ المُنَى

تنْقُلُ الخَطْوَ علَى ما يُرْسَمُ

When fate led scattered hopes in file,

Each step drawn on a destined tile.زُفَراً بيْنَ فُرادَى وثُنَى

مثْلَما يدْعو الوفودَ الموْسِمُ

Alone or in twos they gently came,

Like pilgrims called in season’s name.والحَيا قدْ جلّلَ الرّوضَ سَنا

فثُغورُ الزّهْرِ فيهِ تبْسِمُ

Rain adorned the meadows with light,

And flowers smiled with lips so bright.ورَوَى النّعْمانُ عنْ ماءِ السّما

كيْفَ يرْوي مالِكٌ عنْ أنسِ

As Nu‘mān told of Heaven’s rain,

Like Mālik quoting Anas again.فكَساهُ الحُسْنُ ثوْباً مُعْلَما

يزْدَهي منْهُ بأبْهَى ملْبَسِ

Beauty clothed the earth so proud,

In finest robes, a shining shroud.في لَيالٍ كتَمَتْ سرَّ الهَوى

بالدُّجَى لوْلا شُموسُ الغُرَرِ

Nights that hid love’s secret thread,

But for bright stars overhead.مالَ نجْمُ الكأسِ فيها وهَوى

مُسْتَقيمَ السّيْرِ سعْدَ الأثَرِ

The cup’s star swayed and softly fell,

Its path a blissful, fated spell.وطَرٌ ما فيهِ منْ عيْبٍ سَوَى

أنّهُ مرّ كلَمْحِ البصَرِ

A joy with no flaw, save its flight—

Swift as a blink, lost in night.حينَ لذّ الأنْسُ مَع حُلْوِ اللّمَى

هجَمَ الصُّبْحُ هُجومَ الحرَسِ

Just as delight in sweet lips grew,

Dawn attacked like guards breaking through.غارَتِ الشُّهْبُ بِنا أو ربّما

أثّرَتْ فيها عُيونُ النّرْجِسِ

Did the stars vanish from our sight,

Or did narcissus-eyes dim the night?أيُّ شيءٍ لامرِئٍ قدْ خلَصا

فيكونُ الرّوضُ قد مُكِّنَ فيهْ

What thing is ever fully owned—

Even the garden where dreams are sown?تنْهَبُ الأزْهارُ فيهِ الفُرَصا

أمِنَتْ منْ مَكْرِهِ ما تتّقيهْ

Where flowers steal their fleeting chance,

And trust the plotter’s circumstance?فإذا الماءُ تَناجَى والحَصَى

وخَلا كُلُّ خَليلٍ بأخيهْ

There water whispered to each stone,

And every friend spoke heart alone.تبْصِرُ الورْدَ غَيوراً برِما

يكْتَسي منْ غيْظِهِ ما يكْتسي

See the rose, jealous and disdainful,

Clothed in envy, harsh yet graceful.وتَرى الآسَ لَبيباً فهِما

يسْرِقُ السّمْعَ بأذْنَيْ فرَسِ

And the myrtle, clever and sly,

Stealing ears like a passing cry.يا أُهَيْلَ الحيّ منْ وادِي الغضا

وبقلْبي مسْكَنٌ أنْتُمْ بهِ

O kin of Ghada valley’s grace,

My heart holds you in secret place.ضاقَ عْنْ وجْدي بكُمْ رحْبُ الفَضا

لا أبالِي شرْقُهُ منْ غَرْبِهِ

The wide sky shrinks with longing sore—

East or west, I care no more.فأعِيدوا عهْدَ أنْسٍ قدْ مضَى

تُعْتِقوا عانِيكُمُ منْ كرْبِهِ

Restore the joy of times once dear,

And free your captive from despair.واتّقوا اللهَ وأحْيُوا مُغْرَما

يتَلاشَى نفَساً في نفَسِ

Fear God—and give this lover breath,

Who fades with each exhale to death.حُبِسَ القلْبُ عليْكُمْ كرَما

أفَتَرْضَوْنَ عَفاءَ الحُبُسِ

My heart was jailed for your own sake—

Would you let love’s chains then break?وبقَلْبي منْكُمُ مقْتَرِبٌ

بأحاديثِ المُنَى وهوَ بَعيدْ

You’re close within my longing soul,

Though in dreams, not in control.قمَرٌ أطلَعَ منْهُ المَغْرِبُ

بشِقوةِ المُغْرَى بهِ وهْوَ سَعيدْ

A moon has risen in the west,

Enchanting hearts though in unrest.قد تساوَى مُحسِنٌ أو مُذْنِبُ

في هَواهُ منْ وعْدٍ ووَعيدْ

In his love both fault and grace,

Earn equal joy or stern embrace.ساحِرُ المُقْلَةِ معْسولُ اللّمى

جالَ في النّفسِ مَجالَ النّفَسِ

Enchanting eyes and honeyed lips,

Moved through my soul like breath that slips.سدَّدَ السّهْمَ وسمّى ورَمى

ففؤادي نُهْبَةُ المُفْتَرِسِ

He aimed and named, then loosed the dart—

My heart the prey of his fierce art.إنْ يكُنْ جارَ وخابَ الأمَلُ

وفؤادُ الصّبِّ بالشّوْقِ يَذوبْ

If he turned and hope was lost,

Still my heart melts in passion’s cost.فهْوَ للنّفْسِ حَبيبٌ أوّلُ

ليْسَ في الحُبِّ لمَحْبوبٍ ذُنوبْ

He’s the soul’s first beloved flame—

In love, no guilt bears his name.أمْرُهُ معْتَمَدٌ ممْتَثِلُ

في ضُلوعٍ قدْ بَراها وقُلوبْ

His will obeyed, though ribs grow thin,

And hearts worn down from fire within.حكَمَ اللّحْظُ بِها فاحْتَكَما

لمْ يُراقِبْ في ضِعافِ الأنْفُسِ

A glance passed judgment, swift and raw,

He spared no soul with pity’s law.مُنْصِفُ المظْلومِ ممّنْ ظَلَما

ومُجازي البَريءِ منْها والمُسي

He judged both wronged and guiltless one,

And paid each heart for what was done.ما لقَلْبي كلّما هبّتْ صَبا

عادَهُ عيدٌ منَ الشّوْقِ جَديدْ

Why does my heart, with every breeze,

Relive a feast of longing’s tease?كانَ في اللّوْحِ لهُ مكْتَتَبا

قوْلُهُ إنّ عَذابي لَشديدْ

It’s written in fate’s timeless scroll:

“My torment shall consume the soul.”جلَبَ الهمَّ لهُ والوَصَبا

فهْوَ للأشْجانِ في جُهْدٍ جَهيدْ

He brought me sorrow’s constant weight,

And with grief I strive and wait.لاعِجٌ في أضْلُعي قدْ أُضْرِما

فهْيَ نارٌ في هَشيمِ اليَبَسِ

A burning ache is kindled inside,

A fire in dry twigs that can’t hide.لمْ يدَعْ في مُهْجَتي إلا ذَما

كبَقاءِ الصُّبْحِ بعْدَ الغلَسِ

It left my soul in scornful plight—

Like dawn that scorns the fading night.سلِّمي يا نفْسُ في حُكْمِ القَضا

واعْمُري الوقْتَ برُجْعَى ومَتابْ

Submit, O soul, to fate’s decree,

And fill the time with hope and plea.دعْكَ منْ ذِكْرى زَمانٍ قد مضى

بيْنَ عُتْبَى قدْ تقضّتْ وعِتابْ

Forget the days that once have fled—

Rebuke and sorrow now lie dead.واصْرِفِ القوْلَ الى المَوْلَى الرِّضى

فلَهُم التّوفيقُ في أمِّ الكِتابْ

Turn your speech to God’s good grace,

His decree is clear in Heaven’s place.الكَريمُ المُنْتَهَى والمُنْتَمَى

أسَدُ السّرْحِ وبدْرُ المجْلِسِ

The noble, pure in root and height,

The lion bold, the council’s light.ينْزِلُ النّصْرُ عليْهِ مثْلَما

ينْزِلُ الوحْيُ بروحِ القُدُسِ

Victory comes as angels descend,

Like revelation God does send.مُصْطَفَى اللهِ سَميُّ المُصْطَفَى

الغَنيُّ باللّهِ عنْ كُلِّ أحَدِ

Chosen by God, his namesake blessed,

With God alone—by all else divest.مَنْ إذا ما عقَدَ العهْد وَفَى

وإذا ما فتَحَ الخطْبَ عقَدْ

When he vows, he keeps his word,

When he begins, the task is stirred.مِنْ بَني قيْسِ بْنِ سعْدٍ وكَفى

حيْثُ بيْتُ النّصْرِ مرْفوعُ العَمَدْ

From Qays ibn Sa‘d’s noble line,

Where triumph’s pillars ever shine.حيث بيْتُ النّصْرِ محْميُّ الحِمَى

وجَنى الفَضْلَ زكيُّ المَغْرِسِ

Where glory’s home is well defended,

And virtue’s fruit is richly tended.والهَوى ظِلٌّ ظَليلٌ خيَّما

والنّدَى هبّ الى المُغْتَرَسِ

Love cast its shade so wide, so kind,

And dew came down where roots entwined.هاكَها يا سِبْطَ أنْصارِ العُلَى

والذي إنْ عثَرَ النّصْرُ أقالْ

Take this, O heir of noble stand—

Who lifts up triumph with his hand.عادَةٌ ألْبَسَها الحُسْنُ مُلا

تُبْهِرُ العيْنَ جَلاءً وصِقالْ

A habit draped in beauty’s grace,

That dazzles every searching face.عارَضَتْ لفْظاً ومعْنىً وحُلا

قوْلَ مَنْ أنطَقَهُ الحُبُّ فَقالْ

In word, in form, in taste refined,

As though love’s voice itself had rhymed.هلْ دَرَى ظبْيُ الحِمَى أنْ قد حَمَى

قلْبَ صبٍّ حلّهُ عنْ مَكْنِسِ

Knows the gazelle of the grove he guards,

That he now owns a lover’s heart?فهْوَ في خَفْقِ وحَرٍّ مثلَما

ريحُ الصَّبا بالقَبَسِ

Fluttering, burning, filled with flame—

Like morning’s breeze, in passion’s name.

[1]Covington, Richard (2007). Arndt, Robert (ed.). “Rediscovering Arabic Science”. Saudi Aramco World. 58 (3). Aramco Services Company: 2–16.

[2]Andalusī, Ṣāʻid ibn Aḥmad; Salem, Semaʻan I.; Kumar, Alok (1991). Science in the medieval world: book of the Categories of nations. University of Texas Press. p. 100. ISBN 978-0-292-71139-6. Retrieved 25 May 2013.

[3]El Hour, Rachid. “Jadhwat al-muqtabis fī ta’rīkh ʿulamā’ al-Andalus”. In D. Thomas (ed.), Christian Muslim Relations Online I, (Brill, 2010) doi: https://doi.org/10.1163/1877-8054_cmri_COM_23336.

[4]Vallejo Triano, Antonio (1992). “Madīnat az-Zahrā’: The Triumph of the Islamic State”. In Dodds, Jerrilynn D. (ed.). Al-Andalus: The Art of Islamic Spain. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. pp. 27–39. ISBN 0870996371.

[5]J. Bradford De Long and Andrei Shleifer (October 1993), “Princes and Merchants: European City Growth before the Industrial Revolution” (PDF), The Journal of Law and Economics, 36 (2): 671–702 [678], CiteSeerX 10.1.1.164.4092, doi:10.1086/467294, S2CID 13961320, archived from the original (PDF) on 29 July 2018, retrieved 27 October 2017.

[6]Rāshid, Rushdī; Morelon, Régis (1996). Encyclopedia of the History of Arabic Science: Technology, alchemy and life sciences. CRC Press. p. 945.

[7]S. T. S. Al-Hassani, E. Woodcock, and R. Saoud, 1001 Inventions: Muslim Heritage in Our World, 2nd ed. U.K.: Foundation for Science Technology and Civilization, 2007.

[8]Krebs, Robert E, . Groundbreaking Scientific Experiments, Inventions, and Discoveries of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 95.” Al-Zahrawi (930 or 963–1013 C.E.), also known as Abu-Al Quasim Khalaf ibn’Abbas al-Zahrawi, was a court physician. (2004).

[9]“Abū al-Qāsim | Muslim physician and author”. Encyclopedia Britannica.

[10]Centre, UNESCO World Heritage. “Caliphate City of Medina Azahara”. whc.unesco.org. Retrieved 2018-07-01.

[11]Guichard, Pierre (2013). “Córdoba, de la conquista musulmana a la conquista cristiana”. Awraq (7). Casa Árabe: 5–24. ISSN 0214-834X. Archived from the original on 31 July 2021. Retrieved 31 July 2021.

[12]Arnold, Felix (2017). Islamic Palace Architecture in the Western Mediterranean: A History. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780190624552.

[13]Hamarneh, Sami Khalaf; Sonnedecker, Glenn Allen (1963). A Pharmaceutical View of Abulcasis Al-Zahrāwī in Moorish Spain: With Special Reference to the “Adhān,”. Brill Archive. p. 15.

[14]Vallejo Triano, “Madīnat az-Zahrā’: The Triumph of the Islamic State.”

[15]Guichard, “Córdoba, de la conquista musulmana a la conquista cristiana.”

[16]M. A. Elgohary, “Al Zahrawi: The father of modern surgery,” Ann. Pediatr. Surg., vol. 2, no. 2, pp. 82–87, 2006.

[17]Andalusī, Science in the medieval world.

[18]Ibid.

[19]Arnold, Islamic Palace Architecture in the Western Mediterranean.

[20]S. Amr and A. Tbakhi, “Abu Al Qasim Al Zahrawi (Albucasis): Pioneer of modern surgery,” Ann. Saudi Med., vol. 27, no. 3, pp. 220–221, 2007.

[21]Covington, “Rediscovering Arabic Science.”

[22]I. A. Nabri, “El Zahrawi (936-1013 AD), the father of operative surgery,” Ann. R. Coll. Surg. Engl., vol. 65, no. 2, pp. 132–134, Mar. 1983.

[23]El Hour, “Jadhwat al-muqtabis fī ta’rīkh ʿulamā’ al-Andalus.”

[24]https://madainproject.com/kitab_al_tasrif (2022).

[25]R. Hajar, “Al Zahrawi: Father of surgery,” Heart Views, vol. 7, no. 4, pp. 154–156, 2006.

[26]Vernet, J, [1970-80]. “Ibn Wāfid, Abū Al-Mutarrif ͑Abd Alrahman”. Complete Dictionary of Scientific Biography. Encyclopedia.com. (2008).

[27]M. K. Booz, “Albucasis bone surgery in antiquity,” Pan Arab J. Orthopaed. Trauma, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 73–77, Nov. 1997.

[28]Guichard, “Córdoba, de la conquista musulmana a la conquista cristiana.”

[29]Vallejo Triano, “Madīnat az-Zahrā’: The Triumph of the Islamic State.”

[30]Arnold, Islamic Palace Architecture in the Western Mediterranean.

[31]El Hour, “Jadhwat al-muqtabis fī ta’rīkh ʿulamā’ al-Andalus.”

[32]Ibid.

[33]Ibid.

[34]Ibid.

[35]Ibid.

[36]Ibid.

[37]El Hour, “Jadhwat al-muqtabis fī ta’rīkh ʿulamā’ al-Andalus.”

[38]Ibid.

[39]Covington, “Rediscovering Arabic Science.”

[40]Ibid.

[41]Ibid.

[42]El Hour, “Jadhwat al-muqtabis fī ta’rīkh ʿulamā’ al-Andalus.”

[43]Covington, “Rediscovering Arabic Science.”

[44]Ibid.

[45]El Hour, “Jadhwat al-muqtabis fī ta’rīkh ʿulamā’ al-Andalus.”

[46]Covington, “Rediscovering Arabic Science.”

[47]Ibid.

[48]Ibid.

[49]Ibid.

[50]El Hour, “Jadhwat al-muqtabis fī ta’rīkh ʿulamā’ al-Andalus.”

[51]Covington, “Rediscovering Arabic Science.”

[52]Ibid.

[53]El Hour, “Jadhwat al-muqtabis fī ta’rīkh ʿulamā’ al-Andalus.”

[54]Ibid.

[55]Ibid.

[56]Ibid.

[57]Ibid.

[58]Vallejo Triano, “Madīnat az-Zahrā’: The Triumph of the Islamic State.”

[59]Arnold, Islamic Palace Architecture in the Western Mediterranean.

[60]Covington, “Rediscovering Arabic Science.”