This article seeks to analyse the rise and fall of al-Andalus between 711 and 1492 through the lens of Ibn Khaldun’s cyclical theory of sovereignty. Al-Andalus began as a beacon of civilisation, flourishing under Muslim rule and making remarkable advances in science, art, architecture, and philosophy. However, Al-Andalus gradually disintegrated over 800 years, owing to internal divisions, external pressures, and shifting political dynamics, before ultimately falling in 1492.

Ibn Khaldun’s Theoretical Framework

Ibn Khaldun’s Muqaddimah has provided a theoretical framework that explains the lifecycle of sovereign powers, distilled by scholars into five stages: formation, consolidation, expansion, stagnation, and decline.[1]These five stages can serve as a useful framework for analysing the trajectory of the rise and fall of Al-Andalus. Ibn Khaldun emphasises the role of asabiyya, also known as group feeling or social cohesion[2], in maintaining the survival and success of dynasties. This article argues that the decline of al-Andalus resulted from the progressive erosion of asabiyya, coupled with a shift from growth and expansion to stagnation and ultimate decline. The analysis will focus on the dynastic rules of the Umayyads, Taifas, Almoravids, and Almohads, culminating in the fall of the Nasrids of Granada.

Ibn Khaldun’s Cyclical Theory of Dynasties

Abū Zayd ’Abd ar-Raḥmān ibn Khaldûn al-Ḥaḍramî (1332-1406) was born in Tunisia and is considered a great historian and sociologist of the medieval Muslim world.[3]Ibn Khaldun’s most notable work was his Muqaddima (Introduction to History), in which he analyses the historical development and change of dynasties as a result of transitioning from nomadic culture to urban civilisations.[4] Ibn Khaldun’s cyclical theory regarding the rise and fall of sovereign nations centres on asabiyya, asserting that dynasties generally rise through asabiyya but decline as it diminishes over three to four generations[5], leading to eventual collapse and replacement by a new group with renewed cohesion.

The Concept of Asabiyya and Its Role in State Formation

Asabiyya, for Ibn Khaldun, is the necessity of man to cooperate with his fellow individuals as “social organisation is necessary to the human species. Without it, the existence of human beings would be incomplete”.[6] This emphasises the idea that communal solidarity is not just a social preference but a foundational necessity.

Communal solidarity (ʿasabiyyah) is the binding force that unites individuals into a cohesive group through shared lineage, beliefs, or purpose. It creates trust, loyalty, and a sense of belonging—qualities essential for collective action. Tribal leaders who exhibited strong group feelings were more likely to conquer other nations, build civilisations and sustain control due to the retention of large armies and maintenance of their cultural vigour.[7]For Ibn Khaldun, this solidarity is what enables groups to rise to power, maintain stability, and resist external threats. A leader’s ability to nurture this bond determines the longevity and strength of their political authority. Without it, a society is vulnerable to internal division and eventual decline.

This kinship was considered stronger in tribal areas compared to urban areas, where social cohesion was weaker. This theory envisions that as a nation matures, it transitions into a sedentary life marked by the ascent into luxury, weakening the asabiyya. This contributes to internal conflict and strife, leading to the dynasty’s eventual collapse.

Methodological Approach

While Ibn Khaldun’s model spans one hundred and twenty years, this article will expand these parameters, as eras have been known to go beyond these generational spans, as well as many years within them. Moreover, while Ibn Khaldun’s work serves as an introduction to a broader historical narrative and touches on aspects of al-Andalus, this article applies his methodology more comprehensively to the distinct political, cultural, and spiritual trajectory of Andalusian history.

Stage One: The Foundation of Al-Andalus (711–756)

Introduction and Theoretical Framework

The foundation of Al-Andalus represents the first stage in Ibn Khaldun’s cyclical theory of state development, characterised by conquest, initial settlement, and the strong presence of asabiyya (group solidarity). During this period, leadership tends to be modest, committed to justice, and closely connected to the community. The strong bonds of tribal unity, religious motivation, and mutual loyalty helped the Muslim forces establish and maintain power in the newly conquered territory.

The Muslim Conquest of Iberia (711-712)

Al-Andalus was established by the initial Muslim conquest by the Berber general Tariq ibn Ziyad and the defeat of the Visigothic King Roderic in 711.[8] As Umayyad forces pushed into North Africa between 674 and 709 AD, many native Berber tribes converted to Islam. With their support and growing momentum, an invasion into the Iberian Peninsula became the next logical step in the expansion of Islamic territories[9]. The expedition was initiated by the governor of North Africa, Musa ibn Nusayr, and was led by Tariq ibn Ziyad, with an estimated force of around 12,000 men.[10]

At the time, Iberia was under Visigoth rule, a Germanic tribe whose ruler, Roderic, faced immense pressure and opposition from rival noble factions due to a disputed succession following the death of King Witiza.[11] Roderic’s claim to the throne was contested by supporters of Witiza’s sons, leading to internal strife and fragmentation among the Visigothic elite. This turbulent political environment, compounded by regional loyalties and weak central authority, left the Visigoth kingdom vulnerable.

Additionally, according to the Chronicle of Alfonso III (9th century), some Visigothic aristocrats viewed the Muslim incursion as a chance to settle scores with Roderic, even preferring his defeat. Some nobles were persuaded to cooperate with the Muslims in exchange for retaining lands and privileges, and later, many converted to Islam. This disunity explains why Ibn Ziyad’s army met with little coordinated resistance upon entering Iberia. [12] By 712, Roderic’s army was defeated by Ibn Ziyad, and Cordoba was set up as the new Muslim capital.[13]

Early Settlement and Governance Challenges (712-716)

Muslim settlements in Al-Andalus during the early years lacked a clear administrative system, partly because the conquest was still fresh and leaders had not yet built formal institutions of governance. Although initial settlements in Iberia were haphazard and lacked a solid bureaucracy, cities and villages were still established as the new settlers wanted to procure the new riches of Al-Andalus.[14]

Upon Musa ibn Nusayr’s exit from Al-Andalus, he appointed his son, Abd al-Aziz, as governor. To legitimise his rule, Abd al-Aziz married Roderic’s widow and adorned a crown.[15] This Visigothic pageantry caused consternation amongst his followers, who feared he had converted to Christianity and was about to announce his own monarchy. These rumours ultimately resulted in his assassination in 715-716[16], leaving Al-Andalus without a defined leader.[17]

Asabiyya and the Foundation Stage in Ibn Khaldun’s Framework

The early conquest showed a strong sense of asabiyya—group unity and solidarity. This was seen in how the Muslim forces worked together based on shared tribal values, religious motivation, and mutual loyalty. These bonds helped them hold power and reject anything that seemed to betray their principles, such as Abd al-Aziz’s display of Visigothic customs. The rejection of Abd al-Aziz’s display of Visigoth royal pageantry demonstrated the strength of the asabiyya.

Ibn Khaldun argues that strong group unity keeps societies from falling into luxury and losing their strength. When people become more focused on wealth and comfort, they often lose their sense of responsibility and togetherness, which weakens the foundation of the state.[18] Principles of justice were paramount to the success of any leader. Conversely, exploitation and injustice would increase as levels of luxury grew, leading to the eventual demise and fall of a state[19]. This first period in Al-Andalus reflects what Ibn Khaldun described as the foundation stage of a dynasty. Leaders at this stage tend to be modest, committed to justice, and closely connected to their communities.[20]

Transition and Uncertainty (716-756)

However, Abd al-Aziz’s assassination also revealed how fragile this unity could be. His attempt to appear like a Visigoth king worried many, and the fear that he might abandon Islamic principles led to his downfall. Al-Andalus was left in a state of uncertainty without a clear leader and with only weak ties to the Umayyad Caliphate in Damascus.

This period of uncertainty would continue until the arrival of Abd al-Rahman I in 756, who would establish the Umayyad Emirate and begin the second stage of Al-Andalus’s development, the personalisation of power. The transition from the foundation stage to the next phase demonstrates Ibn Khaldun’s observation that dynasties evolve through predictable patterns, with each stage containing both the achievements of the current period and the seeds of future challenges.

Stage Two: The Personalisation of Power: The Umayyad Emirate (756-788)

Introduction and Theoretical Framework

The personalisation of power refers to the concentration of political authority in the hands of a single ruler, often justified by personal charisma, lineage, or military success rather than broader institutional consensus. In Al-Andalus, this dynamic took shape with the rise of Abd al-Rahman I, the sole surviving Umayyad prince, who established himself as Amir and centralised governance under his control. His leadership marked a transition from fragmented tribal rule to dynastic monarchy, fostering unity among the Muslim population and strengthening asabiyya by rallying diverse factions around a singular, authoritative figure.

The Rise of Abd al-Rahman I

Between 747 and 750, internal upheaval within the Umayyad Caliphate in Damascus culminated in the Abbasid Revolution, during which much of the Umayyad family was massacred. Abd al-Rahman I escaped the purge and sought refuge with his Berber relatives in North Africa. In 755, he crossed into the Andalusian coast and, with the support of Yemeni leaders, assembled an army of approximately 2,000 soldiers. By 756, he proclaimed himself Amir in the mosque of Córdoba, firmly establishing Umayyad rule in Al-Andalus.[21]

Consolidation of Power and Political Strategy

Abd al-Rahman I proved to be an adept tactician and diplomat, successfully defending himself against Abbasid political intrigue by navigating alliances with local Yemeni and Berber factions, quelling internal dissent, and defeating rival claimants such as Yusuf al-Fihri. His ability to unite disparate groups under his leadership and withstand both military threats and political isolation from the Abbasid caliphate highlights his strategic acumen.[22]

According to Diana Darke, the Abbasid Caliph Al-Mansur “is said to have grudgingly given Abd al-Rahman I the exalted title ‘Falcon of the Quraysh’” for his skilful initiatives. Due to his lineage, Abd al-Rahman I was also able to gather support from existing Umayyad residents known as mawali in Al-Andalus.[23] It is important to note that without Abd al-Rahman I’s efforts to unify Al-Andalus during his 33-year reign, the Umayyad name would most likely have been lost.[24]

This unification of Al-Andalus under Umayyad rule serves as a critical foundation for the Andalusian state. While Abd al-Rahman I centralised authority through personal rule, his legitimacy and ability to govern were underpinned by strong asabiyya among the Umayyads and their Berber allies. Rather than conflicting, the personalisation of power in this context was enabled and stabilised by group solidarity, which provided the social cohesion and military loyalty necessary to support his rule and resist both internal rebellion and external Abbasid influence.

Cultural and Architectural Legacy: The Great Mosque of Cordoba

Abd al-Rahman I was deeply devoted to Andalusian political unity but also made great strides towards entrenching Al-Andalus as the capital city. This marks the second stage of Ibn Khaldun’s model, defined by the centralisation of power and the establishment of a royal court. According to Ibn Khaldun, the second stage in the lifecycle of a dynasty is marked by the centralisation of power and the establishment of royal institutions.

Abd al-Rahman I made significant advances in public building and infrastructure, with the mosque of Cordoba being his crown jewel. The initial construction of the mosque took place between 785 and 786 and was constructed over the old Visigoth church of St. Vincent, using many pre-existing Roman and Visigoth stones and columns.[25] Following many extensions, notably by Abd al-Rahman II, with the last being completed in 994, the Cordoba Mosque had the largest covered area among all medieval mosques. This architectural supremacy lasted for four centuries and was only surpassed through the creation of the Sultan Ahmad Mosque in Istanbul in 1607-17.[26]

Upon completion of the Cordoba mosque, it contained 1293 pillars crowned with horseshoe arches in Abd al-Rahman I’s imperial colours of red and white. The mosque’s stone forest demonstrates not just a master of design but unparalleled engineering.[27] A study conducted in 2015 of the mosque’s dome revealed that the vaulting system was a geometric masterpiece, not requiring any structural renovation to date.[28]

Interestingly, during the early 16th century, the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V lamented alterations made to it by Christian architects. Bishop Alonso de Manrique installed a stone chapel for the church choir and invited the emperor to visit[29]. However, upon the visit to the completed project, the emperor noted, “You have built here what you, or anyone else, might have built anywhere; to do so, you have destroyed what was unique in the world.”[30] Thus, even after the Spanish takeover, the Cordoba Mosque still represented a time of political solidity and unmatched cultural splendour.

Personalisation of Power and Ibn Khaldun’s Framework

The reign of Abd al-Rahman I exemplifies Ibn Khaldun’s second stage of dynastic development, where the initial conquest phase transitions to consolidation and institutionalisation. The personalisation of power under Abd al-Rahman I did not diminish asabiyya but rather transformed it, channelling group solidarity toward loyalty to a single ruler and his lineage. This transformation laid the groundwork for the subsequent growth and expansion of the Umayyad state in Al-Andalus while also containing the seeds of future challenges, as the dynasty would eventually move further from its origins of shared hardship and purpose.

STAGE THREE – Growth and Expansion of Umayyad Rule (788-929)

Introduction and Theoretical Framework

As Al-Andalus solidified its power under the Umayyads, it entered a phase of growth, expansion and consolidation of Umayyad rule. Following the death of Abd al-Rahman I in 788, his son Hisham I took over. The rule of Hisham I (788-796) and Abd al-Rahman II (822-852) is characterised by the expansion of defence, formalised administration, and bureaucratic institutions[31]. It is during this stage that a state begins to enjoy stability, increase its influence, and invest in infrastructure and learning. Abd al-Rahman II’s reign reflects this maturity in the state of Al-Andalus, as his rule saw administrative refinement, cultural flourishing, and growing diplomatic and military reach.[32]

The Reign of Hisham I (788-796)

Following the death of Abd al-Rahman I in 788, his son Hisham I took over, carrying on vigorous campaigns, mainly focused on the Frankish territories, including the Asturian kingdom, the Pyrenean region, Gerona and Narbonne.[33]

Arab chroniclers described Hisham I as a pious and ascetic ruler whose authority was exerted through his personal example by leading Muslim forces to victory.[34] According to Kennedy, Hisham had such a “reputation that the great Medinan scholar, Malik B. Anas, whose work so profoundly affected Al-Andalus, is said to have wished that Hisham could make the pilgrimage in person…and be in power over the Abbasid caliphate in Baghdad.”[35] It was during this period that the origins of Malaki jurisprudence can be traced in Al-Andalus[36], primarily due to the visits made by Andalusians to Madina.[37]

The reign of Hisham I also delineates Ibn Khaldun’s third stage of his cyclical theory, through his leadership that extended the territorial reach of Al-Andalus and strengthened its administrative and religious structures.[38] Hisham I maintained the exposure of previous generations through the adoption of an ascetic lifestyle and piety, leading by personal example rather than exerting his authority[39]. His commitment to expansion encompassed the completion of the first phase of the mosque in Cordoba, installing ablution facilities and building the minaret.[40] He also continued robust military campaigns in the Asturias, Upper Ebro, Narbonne and Carcassone in 793, asserting the role of the Umayyads as leaders of all Muslims of al-Andalus.” [41]

The Reign of al-Hakam I (796-822)

His son and successor, al-Hakam, proved to be a more ruthless amir. Ibn Hazm describes him as a public sinner, castrating the children of his subjects and forcing them to be palace eunuchs[42]. Unlike his father, Hisham I, Al-Hakam exemplified the transition into royal authority through the exercise of absolute power over his subjects. The deterioration of asabiyya and social cohesion is reflected in his ruthless reign. Al-Hakam was assassinated in 822, and Abd al-Rahman II succeeded him.

The Reign of Abd al-Rahman II (822-852)

This period marked the expansion of Al-Andalus, as regional governments, laws, and policies were formalised, a structure that persisted until the fall of the Umayyad dynasty. Abd al-Rahman II was the first Andalusian ruler to develop a fully-fledged royal court model. Following the Abbasid civil wars of 811 and 819, Ali bin Nafi, famously known as Ziryab, arrived in Al-Andalus, becoming the arbiter of taste and culture within Umayyad society.[43] Abd al-Rahman II was the most intellectual of Andalusian rulers, encouraging poetry, scholarship and architecture through his extension of the Cordoba Mosque and his patronage of the famed polymath Abbas ibn Firnas.[44]

Institutional Maturity and Cultural Flourishing

According to Ibn Khaldun’s theory, the stage of growth and expansion is characterised by the consolidation of power, the flourishing of institutions, and advancement in cultural and economic life. Abd al-Rahman II proved to be a successful political and military leader. He defeated Viking attacks on Seville, formalised a tax collection system and created tax collectors called the khuzzn[45]. The establishment of a royal court as a centre for culture and intellectual activity represents the change from desert to sedentary life under royal authority. Asabiyya, grounded in shared lineage, military strength, and religious identity, continued to play an effective role in unifying the state and preserving internal stability.[46]

STAGE FOUR – Stagnation: The Umayyad Caliphate (929-1031)

Introduction and Theoretical Framework

Upon the ascension of Abd al-Rahman III (916–961) to the Umayyad throne, Al-Andalus experienced a period of territorial expansion, economic prosperity, and cultural flourishing. However, according to Ibn Khaldun’s theory, such visible growth can paradoxically coincide with internal stagnation. As the state becomes more reliant on bureaucracy and luxury, its founding asabiyya begins to erode. In this phase, rulers increasingly lean on religious symbolism and institutional authority to sustain power rather than the unifying tribal solidarity that once legitimised their rule. Thus, despite outward success, this period marked the early signs of political decline and the eventual fragmentation of Umayyad authority.

Ibn Khaldun argues that the strength and longevity of a dynasty, along with the breadth of its territory, depend on the unity and size of its supporting group.[47] This unity, known as asabiyya (group feeling), must not only be strong within the ruling elite but also widely shared across the broader population to effectively enforce authority and maintain order.[48]. Conversely, when society is divided into competing tribal or political factions, this cohesion weakens. In such fragmented environments, dynasties struggle to sustain power because each group pursues its own interests and claims legitimacy through its own localised form of asabiyya. These multifarious interests, meaning the diverse and often conflicting agendas of smaller factions, create a volatile political landscape where loyalty to a central authority becomes increasingly fragile.[49]

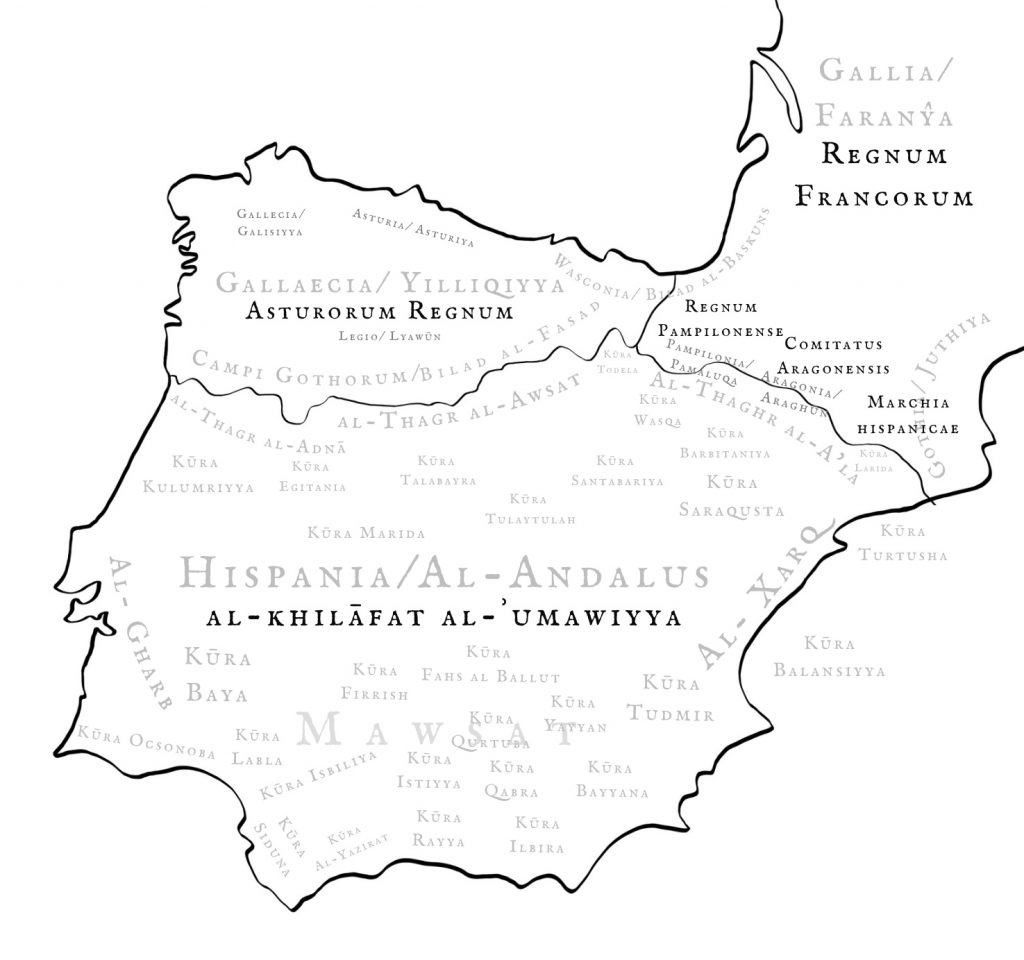

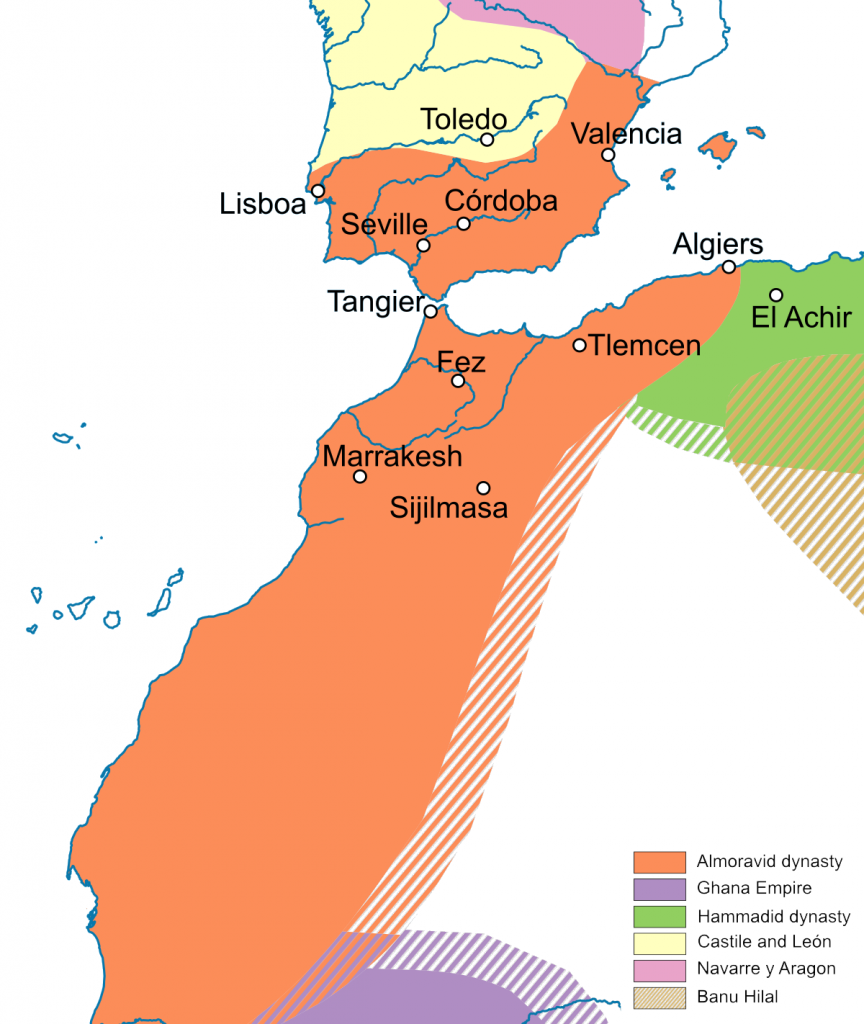

Names are shown in both Latin and Arabic, Names are shown in both Latin and Arabic,

highlighting regional territories and emerging political entities.

The Reign of Abd al-Rahman III (916-961)

Abd al-Rahman III’s primary concerns were the restoration of unity and initiating military campaigns against internal factions. This ended with the surrender of the largest rebel factions of Ibn Hafshun at Bobastro in 928[50]. The first twenty years of Abd al-Rahman III’s rule saw further victories against the northern Christian forces of Leon and Navarre.[51] Although the instability of the northern states of Iberia can be traced to the collapse of the Carolingian empire following the death of Ramiro II of Leon, internal disputes significantly weakened the Christian states, leaving them vulnerable to attacks. By 961, Abd al-Rahman III’s power and influence significantly increased, and his hegemony was recognised by the King of Leon, Queen of Navarre and the Counts of Castile.[52] While the Christian states were not formally part of the dhimmi system, which granted protected status to non-Muslim communities under Islamic rule in exchange for paying the jizya tax and accepting a subordinate political position, they acknowledged Abd al-Rahman III’s suzerainty as quasi-vassals and paid him tribute. This marked the conclusion of the Spanish Umayyad conquests.[53]

Arguably, one of the most significant moments in Abd al-Rahman III’s rule and in the history of Al-Andalus was his assumption of the title of Caliph. In 929, he formally adopted the titles Amir al-Mu’minin and Caliph, placing himself in direct opposition to the Shia Fatimid caliphate and seeking to redirect Sunni religious loyalties toward Al-Andalus. Some historians argue that this declaration was a strategic move to break from the Abbasid caliphate in Baghdad and assert Cordoba’s religious and political independence. Others contend that Abd al-Rahman III’s authority as Caliph was justified by his descent from the Umayyad caliphs of Damascus, framing his claim as a continuation of the original Sunni caliphate.[54]

While Abd al-Rahman III’s declaration of the caliphate appears to be a rejuvenation of the Andalusian asabiyya, it was lost to what Ibn Khaldun would deem a transition to a sedentary and luxurious life. For Ibn Khaldun, “religious propaganda gives a dynasty at its beginning, another power in addition to that of the group feeling it possesses”; however, “religious propaganda cannot materialise without group feeling.”[55] The assumption of a title such as a caliph or the use of holy war to justify conquests at the start of a dynasty is useful during its foundation; however, attempting to hide behind a religious title in the later parts of a dynasty renders its significance ineffective. Abd al-Rahman III’s efforts to stabilise Umayyad rule reached their zenith but would only last one more generation into the rule of his son Al-Hakam II (961-976) [56]

The Reign of Al-Hakam II (961-976)

Despite efforts made by the Christian kingdoms of Castile, Navarre, and Leon to assert independence, they were defeated under Al-Hakam II by the Umayyad force led by General Ghalib.[57] According to Joseph O’Callaghan, the death of Al-Hakam II in 976 “closed the epoch of the greatest splendour in the history of the caliphate of Cordoba”, for the power and prestige once held by the Andalusian Umayyad state would fall into constant decline until the end of Muslim rule in Spain.[58] Ibn Khaldun argues that at the end of a dynasty, rulers will often attempt a last show of power in order to regain some form of prestige, decrying any form of senility.[59] He likens it to “a wick of a flame that leaps up brilliantly a moment before it goes up.”[60] Abd al-Rahman III’s show of power as a caliphate, as well as Al-Hakam II’s final surge against the Christians, represented this final flicker of Umayyad power. Their legacy befell into fitnah[61] extinguishing the candle of Umayyad rule forever.

The Rise of Ibn Abi Amir and the Beginning of Decline

The death of al-Hakam II and the ascension of his eleven-year-old son, Hisham II, laid the groundwork for the Andalusian fitnah, a political civil war that marked the beginning of the final phase of decline in Al-Andalus.[62] Due to his young age, Hisham II’s affairs were managed by the governor of Andalus, Ja’far al-Mus’hafi. However, Hisham II’s mother, Subh, perhaps fearing a lessening of influence, appointed Ibn Abi-Amir, a notorious civil servant, to help oversee the rule.[63] Ibn Abi-Amir slowly enhanced his control over Hisham II by building internal political alliances, allowing him to oust al-Mus’fah by 978. As opposition decreased, he assumed the title of hajib (chief minister or chamberlain).[64] Ibn Abi-Amir consolidated power through the help of jurists. He also indulged the young Caliph, reducing his life to one of feebleness and luxury, which allowed him to assume personal control himself.[65]

As matters escalated, a quarrel between Ibn-Abi-Amir and General Ghalib[66] developed in 981, leading to a battle between them. Although General Ghalib was supported by Christian mercenaries and North African troops, Ibn Abi-Amir ultimately triumphed, leading to Ghalib’s death and Ibn Abi-Amir’s assumption of the title Al-Mansur bil-Allah (Al-Mansur).[67] While Al-Mansur’s dictatorial rule was filled with military action, he died in 1002. Exhausted by the anxiety of his turbulent reign, he was succeeded by his son Abd Al-Malik, who was granted the same powers by the feeble Caliph Hisham II.[68] At this point, the Umayyad dynasty was at its final breath as the short six-year control of Abd Al-Malik would end in 1008, laying the groundwork for one of the most devastating periods in the history of Al-Andalus.[69]

The powerlessness of Hisham II can be understood through the lens of what Ibn Khaldun describes as the final stage of dynastic decline, marked by senility. He writes, ‘Once senility has come upon a dynasty, it cannot be warded off… It is a chronic disorder that cannot be cured or made to disappear because it is something natural, and natural things do not disappear.’ In this phase, dynasties may display brief flashes of strength, giving the illusion of revival, but these are often short-lived, like a wick of a flame that leaps up brilliantly a moment before it goes out.’ [70] In the absence of asabiyya, the internal cohesion and unity that once sustained the Umayyads eroded, making their collapse into political intrigue and fragmentation inevitable.

The Fitnah of Al-Andalus (1008-1031) and the End of Umayyad Rule

The death of Abd Al-Malik spurred the start of the Fitnah of Al-Andalus, which lasted between 1008 and 1031, officially denoting the end of Umayyad rule and the creation of the Taifa states. The fitna encompassed bitter infighting between three contenders for the caliphate, Hisham II, Muhammad II and Sulayman. The struggle began in 1008 when a grandson of Abd al-Rahman III, Muhammad al-Mahdi, deposed the feeble Caliph Hisham II and proclaimed himself Caliph under the name Muhammad II. [71] In response, a group of emerging Berber generals chose Sulayman, another descendant of Abd al-Rahman III, to oppose Muhammad II. They appealed to the Christian state of Castile, to which Count Sancho Garcia responded and defeated Muhammad II in November of 1009, leaving Sulayman as Caliph.[72]

Muhammad II responded through the help of the Count of Barcelona and Urgel, defeating Sulayman, but was later assassinated, re-establishing Hisham II as the Caliph.[73] However, Sulayman continued his struggle for the caliphate. In 1010, he set up a base outside of Cordoba and, along with Berber support, carried out a campaign of destruction and warfare against Cordoba.[74]

This rampage continued for several years until Hisham II surrendered in May 1013. By then, Sulayman had already destroyed the palace of Madinat al-Zahra and its library. He had massacred countless citizens, including fifty scholars, according to the account of the scholar Ibn Hazm.[75] In 1016, another uprising deposed and executed Sulayman, “leading to a number of short-lived puppet caliphs.” [76] Hisham III was the final Umayyad caliph to be expelled in 1031. This period of time is marked by severe violence and corrupt rule, shattering the central hold in Al-Andalus, leading to a fragmented emergence of several successor states called the Taifa kingdoms, or the Muluk al Tawa’if.[77]

The Collapse of Asabiyya and the Rise of the Taifa States

This fragmentation unfolded during the power struggles between Hisham II, Muhammad II, and Sulayman, whose rival claims sparked civil wars and accelerated the collapse of the caliphate. The resulting breakdown in unity led to the rise of the Taifa Kingdoms, independent states that reflected the disintegration of Andalusian asabiyya and the absence of centralised rule.

STAGE FIVE – Decline and Dissolution: The Taifa Kingdoms, Almoravid, Almohad and the Nasrids of Granada

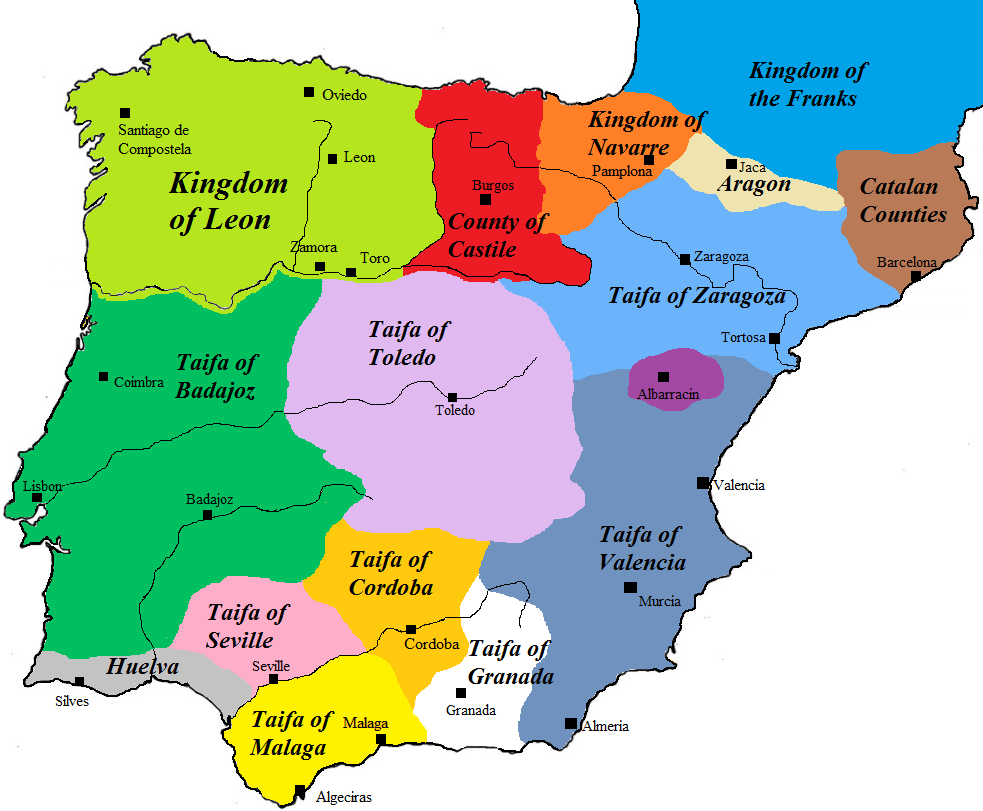

The Taifa Kingdoms: Cultural Flourishing Amid Political Fragmentation

The period of the Taifa states hung between a paradox of cultural flourishing and extreme military and political instability. Plagued with inner fighting and obedience to the emerging Christian states, it eventually led to a takeover by the North African Almoravids. The Taifa rulers had no previous experience of autonomous ruling, mediating disputes or maintaining stable frontiers. The critical period of their instability lasted between 1010-1040, dividing Al-Andalus into over three dozen small states, fighting and conquering each other.[78] Among the statelets, the most prominent included Seville, Granada, Badajoz, Toledo, Valencia, and Zaragoza, with Seville emerging as the most powerful, leaving Cordoba far behind in size and wealth.[79]

While not all Taifa rulers took lofty titles such as king, they instead opted for princely titles or hajib and compensated themselves through virtuous titles like “Al-Mansur” (The Victorious).[80] As their titles became more dazzling, they were criticised, and famously accused of being “cats inflated so as to appear lions”[81] Ironically, the violent disputes between the Taifa states ushered in a rivalry of cultural flourishing, each patronising as many scholars and artists as possible to outdo the other.[82] Poetry from the Almohad court of Seville, for example, exemplifies their hedonistic extravagance, and this luxurious splendour ultimately led to their overindulgence and eventual demise.[83]

Ibn Khaldun notes how successive generations, indulged in luxury, “forget the quality of bravery that was their protection and defence…[and] eventually, they come to depend upon some other militias”[84] This dynamic became starkly evident in 11th-century Al-Andalus. The Taifa rulers, rather than investing in their own military strength, increasingly relied on Christian mercenaries. This reliance began with Catalan support for Muhammad II in 1010 and evolved into a broader pattern of tribute payments, known as parias, in exchange for military protection.[85] [86]

Between 1137 and 1165, the King of Leon and Castille, Fernando I, took tributes from the Taifa princes of Zargizam, Toledo, and Bajonaz[87] The parias paid by the Taifa princes enriched the Christian states, providing a steady income of gold, leaving the Taifa states shackled by the chains of the now advancing Christian kingdoms. By 1085, the last Taifa ruler of Toledo, Al-Qadir, had become wholly ineffective. This allowed the protectorate of the state, Alfonso VI, to interfere with the affairs of the Taifa state, taking advantage of the already existing instability, which stemmed from erratic leadership changes, personal rivalries among Taifa rulers, and the absence of coordinated governance. These internal leadership whims left the state vulnerable to external manipulation, ultimately leading to the fall of Toledo and inciting panic within all of the Taifas.[88]

The Almoravid Intervention and Rule

The Taifas had no other option but to call al-Murabitun (Almoravids), another Muslim power, for their own survival. Established by Yusuf ibn Tashfin, the Almoravids inhabited the southwest fringes of Morocco.[89] They were renowned for the formation of Ribats, similar to Christian monasteries, garnering the name Al-Murabitun (people of the ribat)[90]. The Almoravids later became a derivative of Al-Murabitun, as the language became “corrupted by romance speakers.”[91] The Almoravids were the antithesis of what the Taifa states represented: puritan and simple in lifestyle, speaking very little Arabic.[92]

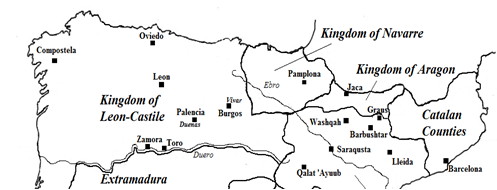

The Taifas, led by Al-Mu’tamid of Seville, called on Yusuf ibn Tashfin to bring his army across the Strait of Gibraltar for military support. On 23rd October 1086, the Almoravids dealt a decisive defeat to Alfonso IV at the Battle of Zalaca.[93]. However, due to anger from the Taifa’s failure to move against the Christians in 1090, Yusuf ibn Tashfin moved against the Taifa states, dethroning Abdallah of Granada and exiling him to Morocco.[94] By 1110, the Almoravids had taken over the Taifa states and swallowed up Valencia and Zaragoza, though Toledo remained under Christian rule.[95] While Al-Andalus was now unified once again, it functioned more as a Moroccan vassal state. This occurred when the Taifa rulers, threatened by Christian advances, invited the Almoravids from Morocco for military support. The Almoravids seized control, integrating Al-Andalus into their empire and ending the tribute payments to Christian kingdoms.[96]

Although the Almoravids initially positioned themselves as saviours of the Muslim lands, they soon succumbed to what Ibn Khaldun describes as the ‘chronic illness of senility.’ He argues that when generations forget their harsh desert origins and toughness, “it is as if they have never existed.”[97] This refers to the natural decline that affects dynasties when rulers become indulgent and detached. Drawn into the luxurious lifestyle of Al-Andalus, they weakened and eventually lost power to another puritanical Berber movement, the Almohads. While the Almoravid authorities may have had genuine religious intentions behind their conquests, their rule was often seen as temporary and full of looting. By the end of Almoravid rule, there were very few original Berber authorities left, as many Andalusian clerics and administrators had been shipped to Morocco.

Ibn Khaldun notes that people who support and establish the dynasty must necessarily be spread throughout the provinces and border regions to protect against enemy rule.[98] Their presence not only ensures the maintenance of social cohesion and group feeling but also allows a royal authority to be channelled through its representatives.[99] As asabiyya declines, luxury and comfort begin to replace discipline and collective duty, weakening the bonds that hold the group together. This was evident as the dissipation of Berber authorities and Andalusian clerks weakened the asabiyya, while the rest of the Almoravid leadership fell into the same indulgent lifestyle that had previously plagued the Taifa states.[100]

This decline provoked the first rebellion against the Almoravids in Cordoba in 1119. By 1125, their hold on Spain was slipping, whilst in Morocco, they were struggling with the newly emerging Almohads.[101] Following the death of the second Almoravid Amir, Ali ibn Yusuf, in 1143, another widespread rebellion occurred in Al-Andalus, causing the Almoravid central power to collapse.[102] The surrounding Christian powers took advantage of this weakness, and Alfonso VII, the grandson of the conqueror of Toledo, Alfonso VI, launched an attack and took over Cordoba in 1146. This reign did not last for long as the Almohads took it back after they crossed into Spain in 1148.[103]

The Almohad Dynasty: Revival and Reformation

The Almohads were another Berber group that rose up to replace what they saw as the corrupt and unfaithful rule of the Almoravids. They aimed to establish a new dynasty based on a revived sense of asabiyya. The founder was Muhammad Ibn Tumart, the son of a chieftain who, during his studies abroad, was influenced by the notable scholar Abu Hamid Al-Ghazali. He returned to Morocco advocating for monotheism and moral reform, criticising the Almoravids for their lax religious practices and aiming to re-establish Islamic governance and society.[104]

The Almohads held similar ideals to the early Almoravids pertaining to the importance of religious reformation. They were characterised by their concept of the unity of God, giving them the title “Al-Muawahhidun” (the unitarians), evolving into Almohads.[105] By 1121, Ibn Tumart was declared the Mahdi by his followers and began their mission of reforming the Almoravids’ piety.[106] According to Firas Alkhateeb, under Almohad rule, “Andalusians refocused themselves on their practice of Islam.”[107] The most notable of the scholars that emerged during Almohad rule was Ibn Rushd, known as Averroes to the West between 1126-1198, a polymath reminiscent of the early Islamic golden age, with his works ranging from psychology to philosophy to physics.[108]

Following the Almohad’s recapture of Cordoba in 1173, all that remained of Al-Andalus had now come under Almohad control.[109] At the height of the Almohad’s power, they conquered Alcocer do Sal and defeated Alfonso VIII in 1191.[110] However, in 1212, the forces of the Almohad Amir Muhammad were defeated by Castillian and Aragonese forces at the Battle of Las Navas de Tolosa, and over a forty-year span, nearly all of Al-Andalus had come under the Kings of Aragon and Castille.[111] In Morocco, another enemy of the Almohads, the Banu Merin, waged war and ultimately defeated and succeeded their authority.[112] Thus, Almohad rule over Al-Andalus came to a close when James I of Aragon and Fernando III of Castile capitalised on the Almohad’s recent military losses and conquered Cordoba in 1236, forever removing it from Muslim hands.[113]

The Nasrids of Granada and the Final Decline.

The defeat of the Almohads was a devastating loss for the Muslim populations of the Iberian Peninsula. Only the Nasrid Emirate of Granada remained relatively free from Christian annexation[114] The Nasrids welcomed the flow of Muslim refugees whose lands had been annexed by Christian forces, representing what would be the beginning of the end of the Muslim Al-Andalus.[115] The Nasrids, however, were not fully independent. Just like their Taifa predecessors, they avoided annexation through military support and tributes in gold from the rich mines of Mali for the Castillians.[116] This system proved very beneficial for the Christian states, enriching them with gold and aiding them in their own conquests. With the absence of two-way trade, only the Christians truly benefited from the Nasrid’s resources until they eventually dried up.[117]

Just as Ibn Khaldun had posited[118] the final spark of the melting candle of Islamic rule is most exemplified through the construction of the Alhambra Palace between 1238 and 1358[119]. A mixture of the Umayyad horseshoe arches, Almoravid and Almohad geometry, courtyards, porticos, fountains and a unique Granadan and Christian style capstone;[120] The Alhambra Palace stood as a striking symbol of the cultural and artistic heights achieved by Muslim civilisation in Iberia. While it can be seen as a unique monument to Andalusian glory, it also emerged during a time of political fragility. For some, its grandeur masked the growing instability of the Nasrid state, the last Muslim stronghold in Al-Andalus. Ibn Khaldun observed that rulers often seek to project strength through luxury and architectural splendour. [121] However, when this pursuit becomes disconnected from the people, it weakens the shared sense of ownership and responsibility. As royal authority becomes more focused on personal grandeur, the collective motivation to defend the state diminishes. [122] The building of lavish palaces like the Alhambra may, therefore, reflect not just power but also the erosion of the communal solidarity and group feeling that were essential to sustaining the state.

According to Ibn Khaldun, as luxury increases, rulers often divert resources from defence and public welfare to maintain their opulence. This leads to higher taxes and financial strain on the wider population. As the communal group becomes economically burdened and loses moral investment in its leaders, the foundational group feeling, or asabiyya, weakens. This decline in solidarity and support accelerates the fall of the dynasty. [123] Although the Alhambra Palace and other architectural achievements symbolised the cultural zenith of Granada, they also imposed heavy financial demands. These projects, while glorious, contributed to the erosion of asabiyya by deepening economic inequality and alienating the population from the ruling elite.”

Just as Abd al-Rahman III’s proclamation marked the final flicker of the flame before the Umayyad dynasty’s collapse, the Nasrid dynasty’s grandeur was the last bright leap before the extinguished candle of Al-Andalus. While Yusuf I’s reign of Grenada was one full of splendour, steeped in architectural marvel and intellectual flourishing, a shadow of instability would forever plague the ruling family of Grenada.[124] Following the assassination of Yusuf I, Muhammad V took over, whose rule was interrupted by a coup in 1359 but restored in 1362 with the help of Peter, the Cruel of Castille.[125] The 14th and 15th centuries were similarly plagued with intrigue within the Nasrid family and an eventual increase in Castilian interference.[126] By 1431, Granada’s defences had been significantly weakened by the Battle of La Higuera against the Castilians, marking a quick decline.[127] The marriage of Isabella of Castille to Ferdinand II of Aragon in 1469 united the two regions over most of the Iberian Peninsula. This created a new wave of hostilities towards Granada, following a crusade called against the Moors after the fall of Constantinople in 1453[128]. The Spanish ‘reconquest’ of Al-Andalus culminated in the formal handover of Granada on 2 January 1492 between Muhammad XII to Isabella and Ferdinand.[129]

The Cyclical Nature of Rise and Fall

The demise of the Taifa and Almoravid states demonstrates Ibn Khaldun’s final cyclical stage of decline and dissolution. These states are given a life of such prosperity and ease that they become dependent upon other dynasties. With the asabiyya completely disintegrating, rulers forget to protect and defend themselves. This can be seen by the heavy reliance on Christian militia by the Taifa states, the eventual decadent spiral of the Almoravids and both states’ inability to stop encroaching forces.

The story of Al-Andalus, when viewed through Ibn Khaldun’s cyclical theory, reflects the rise and fall of dynasties in five phases: foundation, consolidation, expansion, stagnation, and decline. This historical arc reveals a civilisation of immense brilliance yet also of inherent impermanence, as no dynasty escapes the natural decay built into its own success. Al-Andalus was born from the unity and strength of asabiyya, flourishing into a powerful and vibrant civilisation. However, as Ibn Khaldun cautioned, the very prosperity it achieved led to its downfall. The increasing luxury and comfort enjoyed by the elite eroded group solidarity, distancing rulers from their people and weakening the internal cohesion necessary for defence and stability.

From the foundations laid by Tariq ibn Ziyad to the Golden Age of Umayyad unity, Al-Andalus maintained a strong sense of asabiyya. Although the Taifa kingdoms, the Almoravid, Almohad and Nasrid reigns, each sought to revive Al-Andalus’ fading glory, division and dependence on foreign allies only hastened its decline. In 1492, the fall of Granada marked the final extinguishing of the Andalusian flame. To this day, the Andalusian legacy is woven into the fabric of Spain, Europe, and the wider world. The mosque of Cordoba and the Alhambra Palace continue to bear witness to the lost grandeur of Al-Andalus, preserving its enduring influence in the fields of art, science, and philosophy. Although the ever-turning wheel of time exposes the fragile nature of dynastic rule, Al-Andalus will always remain a great example in Muslim history as a state that demonstrates unity, growth and communal values.

[1] Önder and Ulaşan, 237

[2] Linda T. Darling, “(“Asabiyya”) and Justice in the Late Medieval Middle East,” Comparative Studies in Society and History, vol.49, No. 2(Apr.,2007) pp.329

[3] Pišev, Marko, 2019. “Anthropological Aspects of Ibn Khaldun’s Muqaddimah: A Critical Examination”, Bérose – Encyclopédie internationale des histoires de l’anthropologie, Paris.

[4] Darling, pp.329-357: 329.

[5] Murat Önder and Fatih Ulaşan. “Ibn Khaldun’s Cyclical Theory on the Rise and Fall of Soveriegn Powers: The Case of Ottoman Empire.” Adam Akademi Sosyal Bilimler Dergisi, Adam Academy Journal of Social Science 8, no. 2 (2018) pp231-266: 235

[6] Ibn Khaldūn. The Muqaddimah : An Introduction to History. Edited by N. J. Dawood. Translated by Franz Rosenthal. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2020, 46

[7] Darling, 329

[8] Roger Collins, The Arabic Conquest of Spain 710–797(Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1994), pp. 17–22; It is essential to note the absence of surviving contemporary Arabic sources of these initial conquests, as the earliest significant Muslim sources appear after the tenth century. The anonymous Latin Chronicle of 754 is therefore more commonly used due to its more contemporary timeline. See Hugh Kennedy, Muslim Spain and Portugal : A Political History of al-Andalus. London: Routledge, 2014, 7 and Fletcher, Richard. Moorish Spain, London: Phoenix Press, 2001.

[9] Hugh Kennedy, Muslim Spain and Portugal : A Political History of al-Andalus. London: Routledge, 2014, 3

[10] Richard Hitchcock, Muslim Spain Reconsidered: From 711 to 1502. Edinburgh University Press, 2014, 20

[11] Mahmoud Makki. “The Political History of al-Andalus (92/711-897/1492)”. In The Legacy of Muslim Spain, (Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill, 1992) 6

[12] Kennedy, 11

[13] Kennedy, 11, 16

[14] Kennedy, 16-18

[15] Ana Ruiz, Medina Mayrit, The Origins of Madriid, New York: Algoria Publishing 2012, 28

[16] Ruiz, 28

[17] Hitchcock, 27

[18] Khaldun, 109

[19] Darling, 329

[20] Önder and Ulaşan, 137

[21] Kennedy, 13

[22] Diana Darke, Stealing from the Saracens : How Islamic Architecture Shaped Europe. London: Hurst & Company, 2020. 156-157

[23] Kennedy, 32

[24] Hitchcock, 43

[25] Darke, 160.

[26] Darke, 164

[27] Richard Ettinghausen, Oleg Grabar and Marilyn Jenkins-Madina, Islamic Art and Architecture 650-1250, Yale University: Press Pelican, 2001, 89

[28] Darke, 174

[29] Richard Fletcher, Richard. Moorish Spain, London: Phoenix Press, 2001, 3

[30] Fletcher, 3

[31] Janina M. Safran, Defining Boundaries in Al-Andalus: Muslim, Christians and Jews in Islamic Iberia, Cornell University Press 2013, 43

[32] Khaldun, 137

[33] Hitchcock, 48

[34] Kennedy,40

[35] Kennedy, 40

[36] Muhammad Akmaluddun, International E-Journal of Advance in Social Sciences, Vol. III, 9, 2017, pp.880-887, 885

[37] Hitchcock,48

[38] Ibn Khaldun, 137

[39] Kennedy,

[42] Cristina de le Puente, “Al-Hakam I in the Andalusi Sources: His Salve, Eunuchs and Concubines”, Slavery & Abolition, Vol. 44, No, 4, pp. 593-615, 615

[43] Makki, 26

[44] Glaire D Anderson, “Mind and Hand: Early Scientific Instruments From Al-Andalus, and ‘Abbas ibn Firnas in the Cordoban Umayyad Court”, Muqarnas, 2020-01, Vol.37 (1), pp.1-28,3

[45] Hitchcock, 57

[46] Önder and Ulaşan, 257

[47] Ibn Khaldun, 129

[48] Ibn Khaldun, 128

[49] Ibn Khaldin, 130

[50] Joseph F O’Callaghan, A History of Medieval Spain. Cornell University Press, 1983, 117.

[51] William Montgomery Watt and Pierre Cachia. A History of Islamic Spain. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press (2007), 41

[52] Watt,41

[53] Watt, 42

[54] O’Callaghan, 118

[55] Khaldun, 126-127

[56] Watt, 46

[57] O’Callaghan, 125

[58] O’Callaghan 126

[59] Khaldun, 246

[60] Khaldun, 246

[61] Arabic word for strife and also refers to the civil wars within the Umayyad Caliphate of Cordoba. See Stephen Baxter, Navigator: Time’s Tapestry:3, New York: Penguin Group, 2007, 40.

[62] The term fitnah in Islamic history refers to a period of severe trial, discord, or civil strife. In this context, it describes the internal political turmoil and conflict that fractured the unity of the Umayyad Caliphate in Al-Andalus, often referred to as the Andalusian Fitnah (1009–1031 CE).

[63] Watt, 81-2

[64] O’Callaghan, 127. The term Hajib refers to a high ranking official such as a chamberlain. Under the Spanish Umayyad’s the hajibs were likened to a chief minister. However, Ibn Abi Amir used the title hajib as a ruse to disguise his authoritarian rule. See The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. “ḥājib.” Encyclopedia Britannica, July 20, 1998. https://www.britannica.com/topic/hajib.

[65] Watt, 82

[66] Ghalib was also a general under the rule of al-Hakam II and became the father-in law of Ibn Abi-Amir. See Joseph F O’Callaghan, A History of Medieval Spain. Cornell University Press, 1983.

[67] O’Callaghan, 128

[68] Watt, 84

[69] Watt, 85

[70] Khaldun, 245

[71] Makki,47

[72] O’Callaghan, 132

[73] Makki, 48

[74] Fletcher, 80

[75] Fletcher, 81

[76] Fletcher 81

[77] Fletcher, 81

[78] Makki, 50

[79] Hitchcock,114

[80] Viguera-Molins, María Jesús, and Maribel Fierro. “Al-Andalus and the Maghrib (from the Fifth/Eleventh Century to the Fall of the Almoravids).” In The New Cambridge History of Islam, 2:19–47. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000, 28-29

[81] Viguera-Molins et al, 29

[82] Fletcher, 88

[83] Fletcher, 90

[84] Khaldun, 135

[85] Fletcher, 98

[86] Viguera-Molins et al, 28

[87] Hitchcock, 122

[88] Javier Albarrán, João Gouveia Monteiro, and Francisco García Fitz. “Al-Andalus.” In War in the Iberian Peninsula, 700-1600, 1st ed., 1–35. United Kingdom: Routledge, 2018., 4

[89] Amira K Bennison, The Almoravid and Almohad Empires. Edinburgh University Press, 2016, 1-2

[90] H.T Norris, “New Evidence on the life of Abdullah B. Yasin and the Origins of the Almoraivd Movement”, The Journal of African History, Vol.12 No. 2 (1971) pp. 255-268, 262-265

[91] Viguera-Molins et al, 37

[92] Fletcher, 108

[93] Javier Albarrán et al, 5

[94] Bennison, 47

[95] Fletcher, 111

[96] Javier Albarrán et al, 5

[97] Ibn Khaldun,137

[98] Ibn Khaldun, 128

[100] Javier Albarrán et al, 5

[101] Fletcher, 118-119

[102] Fletcher, 121

[103] Fletcher,121

[104] Bennison, 64

[105] Bennison 65

[106] Bennison, 65

[107] Firas Alkhateeb, Lost Islamic History : Reclaiming Muslim Civilisation from the Past. Revised and Updated version. London: Hurst & Company, 2017, 156

[108] Alkhateeb, 156

[109] O’Callaghan, 228

[110] O’Callaghan, 243

[111] O’Callaghan, 243

[112] Fletcher 126

[113] Fletcher, 128

[114] Alkhateeb,158

[115] Alkhateeb, 158

[116] Alkhateeb, 158

[117] Alkhateeb,159

[118] Ibn Khaldun, 246

[119] Jerrliynn Dobbs, Al-Andalus: The Art of Islamic Spain, New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, (1992)11-25

[120] Alkhateeb, 159

[121] Ibn Khaldun, 133

[122] Ibn Khaldun, 134

[123] Ibn Khaldun, 135

[124] Helen Rodgers and Stephen Cavendish. City of Illusions: A History of Granada. Oxford University Press, 2021.,77

[125] Rogers and Cavendish, 88

[126] Rogers and Cavendish, 91

[127] Rogers and Cavendish, 92

[128] Rogers and Cavendish, 98

[129] Rogers and Cavendish,114