Al-Andalus: A Unique Synthesis of East and West

Al-Andalus represents one of the most successful amalgamations of Eastern and Western philosophy in the history of human civilisation before the advent of the modern era. It was a Western world dominated by the culture and religion of Islam; that is, it depicted a representation of “Western Islam” or an Islamified Europe. It served as a medium for scientific exchange between the Islamic and Christian worlds and between Arab and Roman cultures.[1] During this era of Andalusian Islam, a level of achievement was reached that one could argue has not been surpassed since. By studying and analysing Andalusian Islam, we may find a window of opportunity into a potential religious and secular utopia. Al-Andalus uniquely blended secularism with religion in a way that neither diminished religion nor forced secularism aside. Rather, it allowed Muslim scientists, philosophers, theorists, theologians, spiritualists, and religious scholars to push the boundaries of exploration and scientific development.

Al-Andalus challenges some of the most vicious modern-day biases and stereotypes that critics of Islam hold. Modern critics sometimes postulate that Islam is a forceful religion, spread by the sword without care for human life and void of empathy. However, Al-Andalus represents a geographic, cultural, and religious area which, though ruled by Muslims for the vast majority of its 800-year history, was never a Muslim majority. While a few major urban areas (e.g., Córdoba) were at most 70% Muslim (near the end of Muslim rule over Al-Andalus), most of the landscape, which was dominated by rural lands, was populated by a community that was typically over 80% non-Muslim.[2] Yes, the ruling elite were Muslims, and the leadership was Muslim (i.e., the Caliphate), but Christians, Jews, and those of any background could live securely and happily without fear of persecution under Muslim rule. No doubt, it was this security and safety that allowed scientists to work freely and enabled the intermingling of great minds, regardless of background, religion, caste, or upbringing.

The Intellectual Legacy of Andalusian Islam

Andalusian Islamic history serves as an inspiration. It produced some of the best and brightest minds in Islam (perhaps ever in the history of Islam after the time of the Prophet (SAW), the Sahaba, Tabi’een, and Tabi Tabi’een) who rose from a society where they grew up amongst a population that was not dominantly Islamic. Al-Andalus represents a time when Islamic scientists were at the forefront, and most textbooks taught in the Roman, Greek, and much of the known world used Arabic textbooks (translated into Latin). The brightest thinkers would find their way to Al-Andalus to partake in the scientific revolution underway throughout the region. The remnant of that revolution can be seen to this day, even after a thousand years. Regrettably, over the last 1000 years or so, Islamic advances have been hidden, albeit in plain sight, because of the gradual decline of Islam with respect to scientific and technological advancement. In fact, certain common and scientific words in use in the mainstream English language today are actually from Arabic culture, and some from the Andalusian times.

Hidden Islamic Contributions to Modern Language and Science

As time progressed and Islamic empires regressed, many of the contributions of Islamic scientists, theologians, philosophers, and thinkers began to be forgotten or were so westernised that one could not make the connection between the modern world or principle and its Islamic root. For example, coffee comes from the Arabic word qahwa, zero from the Arabic word sifr, algebra from al-jabr, algorithm via the Latinization of the Islamic scholar Al-Khwarizmi, admiral from amir-al-bahr, apricot from al-birquq, zenith from samt al-ra’s, nadir from nazir as-samt, abdomen from the Arabic word al-baden, and cornea from qarniyya.

The article authored below cracks that window into the rich history of Andalusian Islam to showcase just one such legend of Islam who not only served his religion but also humanity: Al-Zahrawi.

Perhaps due to the loss of the Andalusian libraries and the pitfalls of time, many have forgotten the profound impact Al-Zahrawi has had in shaping modern medicine and surgical procedures.

The Science of Al-Andalus & Contemporaries of Al-Zahrawi

Before we dive into the contributions of Al-Zahrawi, it is important to understand a brief history of Al-Andalus. Over a span of approximately 800 years (the exact inception and decline of Al-Andalus vary from historian to historian, but roughly from 711 AD to 1492 AD), Al-Andalus emerged as a centre of culture, economics, philosophy, and, as it pertains to this article, science. During this time, Muslim scientists and physicians made substantial advances in technology, chemistry, and biology. It would not be an over-assumption to state that these Andalusian scientists and physicians helped bridge the gap between ancient and modern scientific and medical advances; without them, the modern landscape of medicine and science may have been vastly different. Several notable Andalusian Muslim scientists joined Al-Zahrawi during this time in bringing about the coveted “Golden Age of Islam.” These include:

- Jabir ibn Aflah: Credited as one of the founders of modern-day trigonometry, he corrected the orbits of Mercury and Venus, which had been calculated by his Greek predecessors.

- Al-Zarqali: An individual revered to this day for his astronomical analysis and inventions. A crater on the moon (Arzachel) is named after him.

- Ibn Zuhr: Known as one of the founders of modern pharmacology and one of the first recorded scientists to stress the importance of diet by deducing the nutritional benefits of different types of foods.

- Ibn Bassal: Considered by many as the father of modern-day botany.

- Abu’l-Khayr al-Ishbili invented many of the agricultural and agronomical methods that dominated the rural landscape for the next 700 years.

- Ibn al-Wafid: One of the earliest known pharmacologists, he is credited with having extracted at least 520 different types of medicines from various plants and herbs.[3] He collaborated with Al-Zahrawi on more than one occasion for the treatment of several diseases.

- Maslama ibn Ahmad al-Majriti: A mathematician and astronomer considered by many to be the best of his time in Al-Andalus.[4] He is credited as a pioneer in collaborative scientific research and built one of the earliest known schools of Astronomy and Mathematics. It is thought that he had a significant impact on Al-Zahrawi as he authored his Al-Tasrif.[5]

Note: This is a very small list of Muslim scientists of that era, intended simply to showcase the rich culture of scientific advancement and the vibrant scientific landscape of Andalusian Islam.

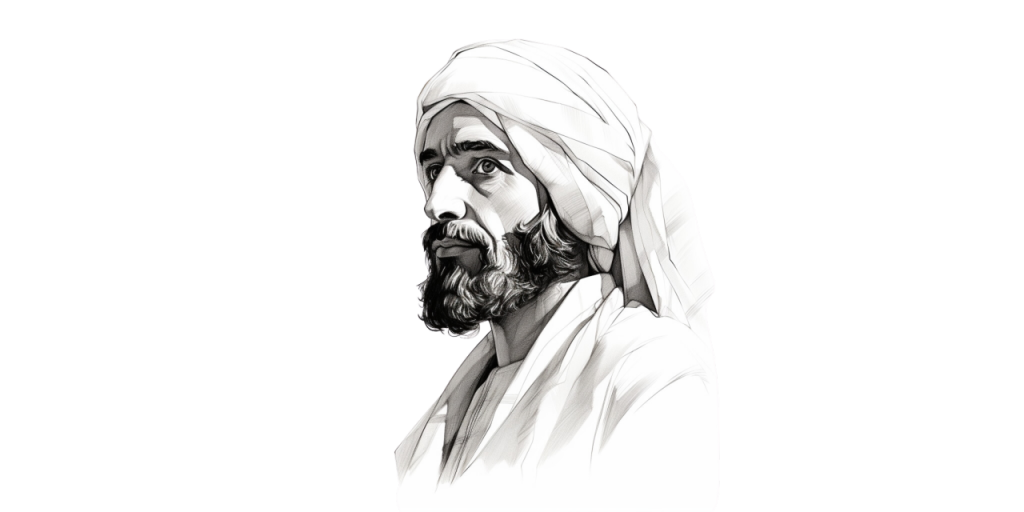

Introduction to Al-Zahrawi

Abu Al-Qasim Khalaf ibn Al-Abbas Al-Zahrawi Al-Ansari, or more commonly referred to as Abulcasis, Albucasis, Zahravius, Az-Zahrawi, or Al-Zahrawi,[6] was born in a small city on the outskirts of Córdoba, Andalusia, Spain, in approximately 936 AD (324-325 Hijri). Of Arabic ancestry, historians speculate his family originated from the Ansar tribe of Medina-tul-Munawara (in the Arabian Peninsula) due to his nisba of Al-Ansari.[7] Coincidentally, the city in which he was born, Medina Azahara, was founded the same year as his birth.[8] Historians believe this city was named after Medina-tul-Munawara. This small city served as the summer residence of the Umayyad Caliphs and was also the place where Al-Zahrawi would eventually be appointed as the court physician of the Andalusian Caliph Al-Hakam II.. [9] A street in Córdoba is named “Calle Albucais” in his honour—a testament to his vast influence on Al-Andalus and modern science and medicine.[10]

While very little is known about Al-Zahrawi’s early education, it is speculated that he realised physicians had very rudimentary knowledge of cautery and cauterisation, which caused pain and unnecessary (sometimes fatal) blood loss while treating ulcers, infections, and wounds. Ibn Hazm noted that his early experiences with patients dying due to unnecessary blood loss, combined with his empathetic nature, likely caused him to devote most of his life to expanding his knowledge of anatomy and surgical procedures, eventually pioneering modern practices.[11]

Al-Zahrawi is considered one of, if not the greatest, surgeons of the Middle Ages. Most also consider him the first of a small line of genius Muslim surgeons who dominated the medicinal landscape from the late 900s through to the early 1200s.

Among his many achievements are:

- Father of modern-day surgery.

- Father of operative surgery.[12]

- Pioneer of modern cauterisation procedures.[13]

- Completed the first thyroidectomy (surgical removal of all or some part of the thyroid gland).[14]

- Completed the first tonsillectomy using instruments that closely resembled modern surgical instruments.

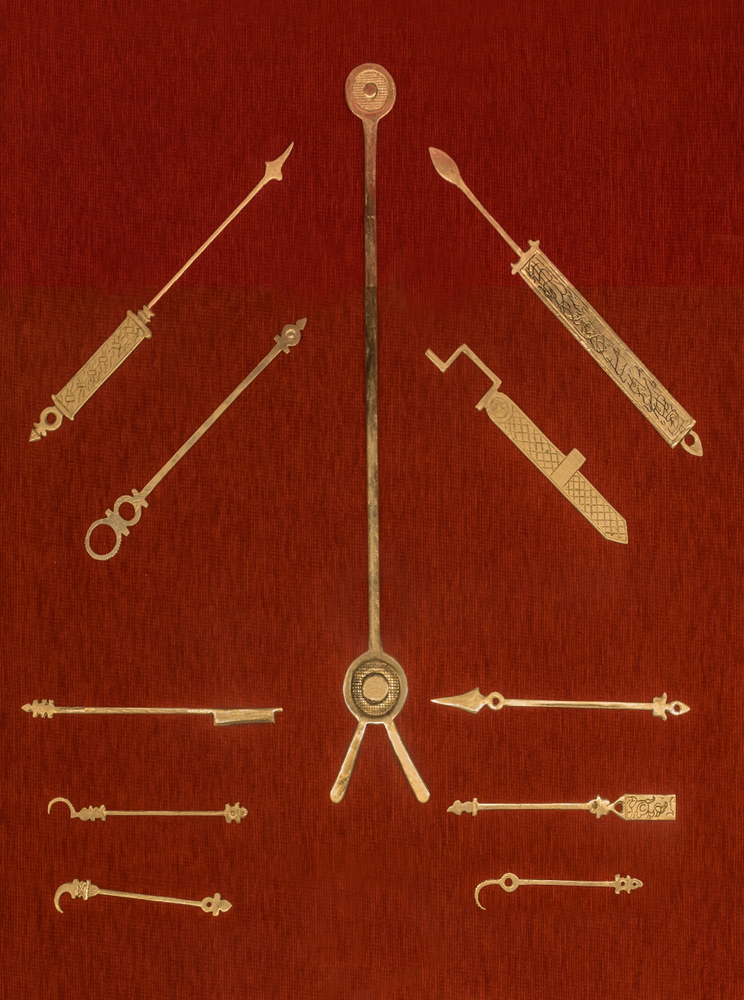

- Invented over 100 different types of surgical instruments.[15]

- Pioneer of pediatric neurosurgery.[16]

- Pioneer of Biomedical Engineering.[17]

- Pioneer of genetics and hereditary behaviour, especially as it pertains to haemophilia.[18]

The Personality & Character of Al-Zahrawi

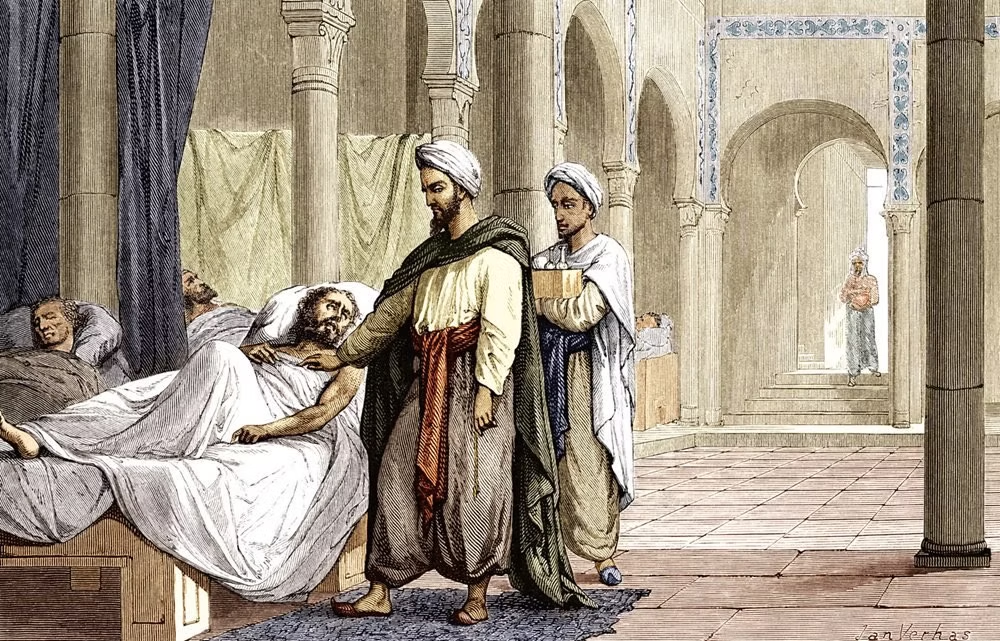

Though very little is known of his life and personality (due to the sacking and destruction of many of the libraries in Andalusian Spain and his hometown of Medina Azahara), there are several accounts of his exemplary character and akhlaq. Notably, Ibn Hazm (993-1064) dedicates a chapter to Al-Zahrawi in his book “Jadhwat al-Muqtabis” (Translation: On Andalusian Servants).[19] As was common amongst the early Muslim Andalusian scientists, stories of Al-Zahrawi’s humanity and caring nature have become the stuff of legend. Al-Zahrawi is noted to have spent over half of his daily working hours treating patients as an unpaid volunteer.[20] On several occasions, he is documented to have served and cured slaves, captives, and runaways without discriminating between the wealthy and the poor.[21] He often paid for bright students under his own tutelage to receive the best education and then guided them towards the medical profession.[22] Interestingly, he often referred to his students as his sons, and historians note that his relationship with his students was less like a teacher and more like a father. This account represents a significant early record of a Muslim murshid (teacher) having a pseudo-paternal relationship with his murideen (students). While there may have been other cases in both secular and religious sciences before Al-Zahrawi, and post-1000 AD, there are several accounts of scholars using “sons” to refer to their muridee;, this appears to be among the first recorded authentic sources that documents a teacher-student relationship in this manner.

The scientific influences of Al-Zahrawi were mainly Abu Bakr al-Razi (a Persian physician widely regarded as one of the most important figures in the history of medicine, the father of pediatrics, and a pioneer of obstetrics and ophthalmology)[23] and Ibn al-Jabbar (a Tunisian physician who pioneered medical advances in women’s diseases and pediatrics and who dedicated his life to serving the poor, having written the book Tibb al-Fuqara [Medicine for the Poor]).[24]

There are virtually no resources available that speak to his religious upbringing or religious studies. However, as per the saying of Umar ibn al-Khattab (as recorded in Az-Zuhd of Imam Abu Dawud, Hadith: 89), “Assume the best about your brother until what comes to you from him overcomes you (and you have to change your opinion).” One must also consider that his religious influences were likely significant, as he was literally born in a city named after the “City of the Prophet” (i.e., Medina al-Munawwara).

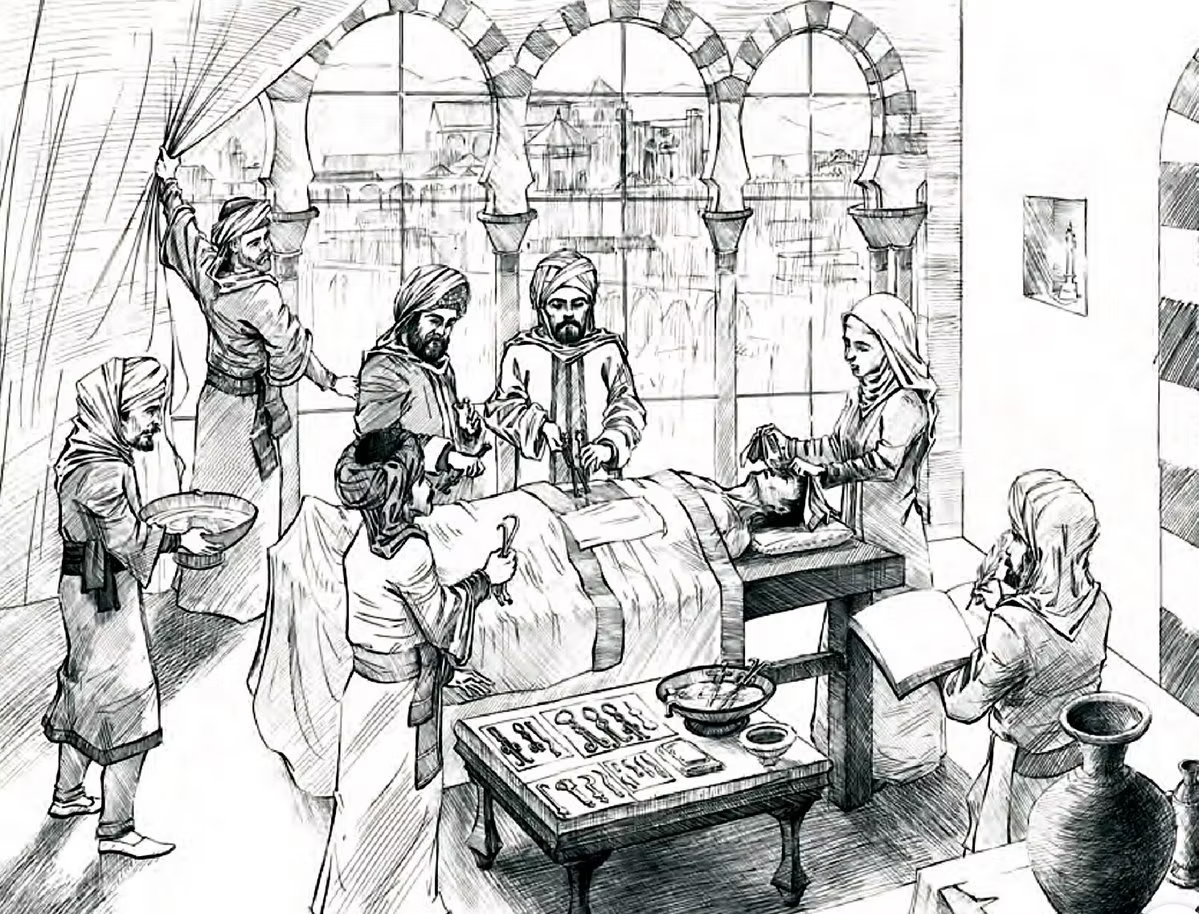

He took extreme care when treating patients and regarded surgery as supremely important. He understood the dangers of surgery and that the smallest mistake in even the simplest of procedures could prove fatal for the patient. This fact is evident when his Kitab al-Tasrif is studied: he is noted to have said that he chose to discuss surgery in the last volumes of his encyclopedia as he considered surgery the pinnacle of medicine and believed it should only be performed by a physician who has become well-acquainted with all the other branches of medicine.[25] Another direct quote attributed to Al-Zahrawi, which highlights his empathy as well as his profound understanding of operative surgery, is: “[Surgery] should not be attempted except by one who has a good knowledge of the anatomy of the limbs and of the exits of the nerves that move the body.”[26] Furthermore, Al-Zahrawi paid extremely close attention to hygiene and cleanliness. Notably, it was he who first used alcohol (extracted from wine) to keep surgical instruments clean and free from infection and bacteria.[27] Lastly, he was the first to implement the use of spare tools during a surgical procedure in case of an emergency.[28]

Kitab al-Tasrif

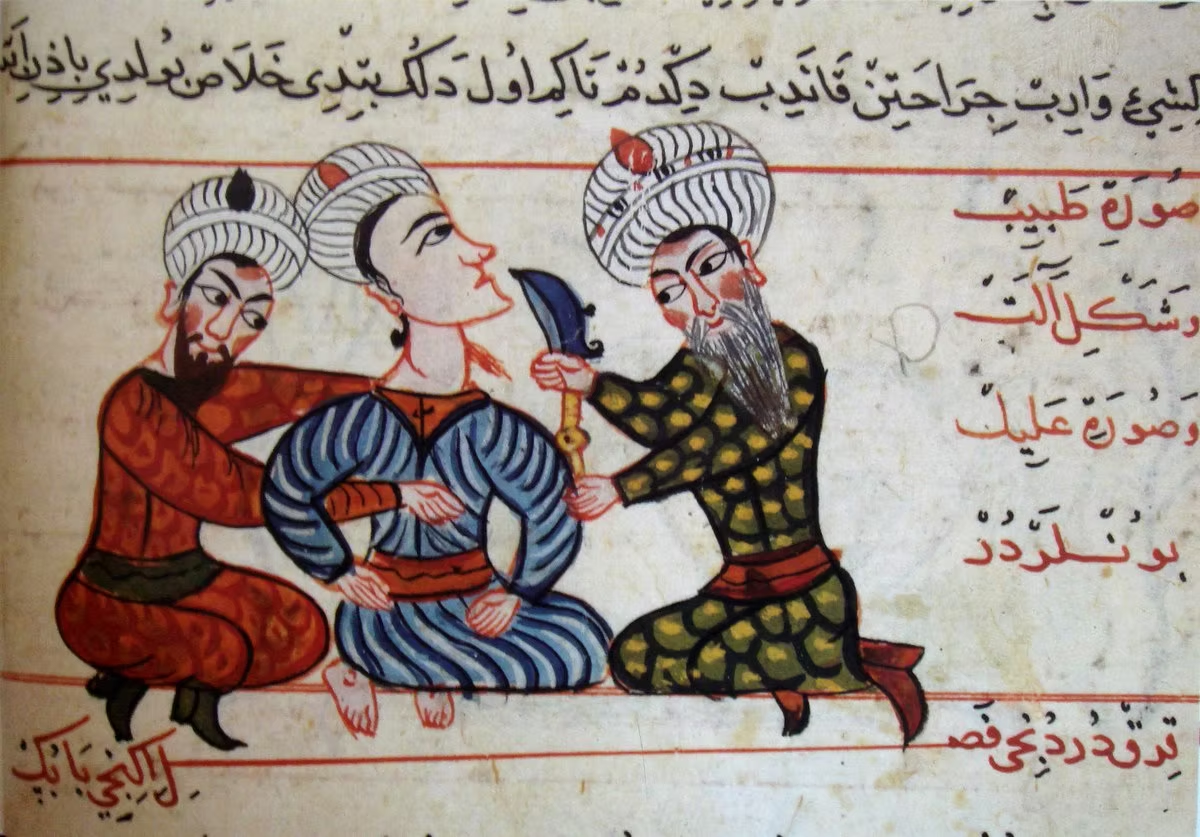

Perhaps the defining feature of the life of Al-Zahrawi is his encyclopedia: Kitāb al-Taṣrīf li-man ‘ajaza ‘an al-ta’līf fi al-tibb (كتاب التصريف لمن عجز عن التأليف في الطب) (translation: The Arrangement of Medical Knowledge for One Who Is Not Able to Compile a Book for Himself: On Surgery and Instruments). This book is more commonly referred to as Kitab al-Tasrif (Method of Medicine) or al-Tasrif for short, and became the dominant standard textbook for medical education, surgical instruments, and surgery throughout the world for the next 500 years. Some defining features of this encyclopedia are listed below:

• Authored in approximately the year 1000 AD[29] • Consists of 30 volumes with information on midwifery, pharmacology, dietetics, psychotherapy, weights, measures, medical chemistry,[30] various illnesses, injuries, medical conditions, treatments, and surgical procedures[31] • Describes over 200 different surgical instruments[32] of which at least 100 were invented by Al-Zahrawi himself • Three volumes dedicated exclusively to surgery and surgical procedures, with the last treatise exclusively on the use of surgical instruments[33]

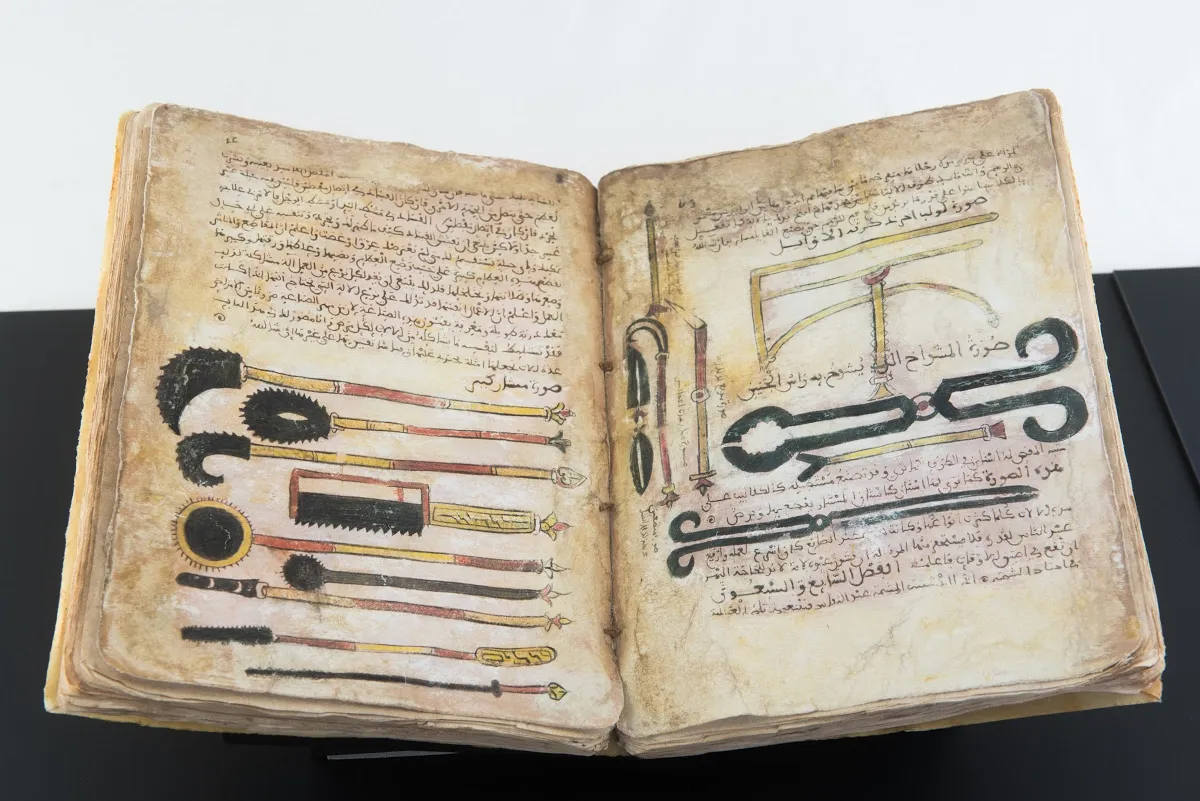

Note: A page of the Kitab al-Tasrif is depicted in Figure 1 from the Patna Manuscripts.

Figure 1: A manuscript of Kitab al-Tasrif in the Public Library in Patna (Also known as the Patna Manuscript). It shows the level of discipline and detail that Al-Zahrawi demonstrated when writing his al-Tasrif.[34]

Contributions of Al-Zahrawi to Medicine & Surgery

Important Surgical Inventions of Al-Zahrawi

Several important inventions are attributed to Al-Zahrawi in this section. Interestingly, there are also several inventions listed below for which credit has been given to scientists who came centuries later, when in fact Al-Zahrawi should have been credited with their actual inception. Note that the inventions listed below are only some of the inventions of Al-Zahrawi which are still in use today. There are dozens more which were in use for centuries afterwards but recently became obsolete with technological advancements (e.g., cephalotribe).

Modern Day Catheter

While the first catheter was introduced by Galen about 700 years before Al-Zahrawi,[35] it was in fact Al-Zahrawi who developed the first catheter that resembled the catheters in use today. Galen’s catheter was S-shaped,[36] while Al-Zahrawi’s was straight with a funnelled end as shown in Figure 2. He named this invention the “mirwed” and used it to inspect the urethra for any blockages.[37]

Figure 2: Straight Catheter for urinary bladder irrigation.[38]

Forceps

Al-Tasrif lists the first actual practical use of forceps in surgical procedures. They were described as being used in bladder irrigation in the event of kidney stones to crush them and allow them to excrete naturally.[39]

Scalpel

While scalpels existed from the time of the Greeks (i.e., Archigenes of Ephesus), it was the Al-Zahrawi scalpel that most closely resembles the scalpels in use in modern surgical theatres today, with one flat side and one sharp side.[40] The original design of Al-Zahrawi remained unchanged for the next 800 years, when the next modification was made by Andreas A. Cruce in the 18th century.[41]

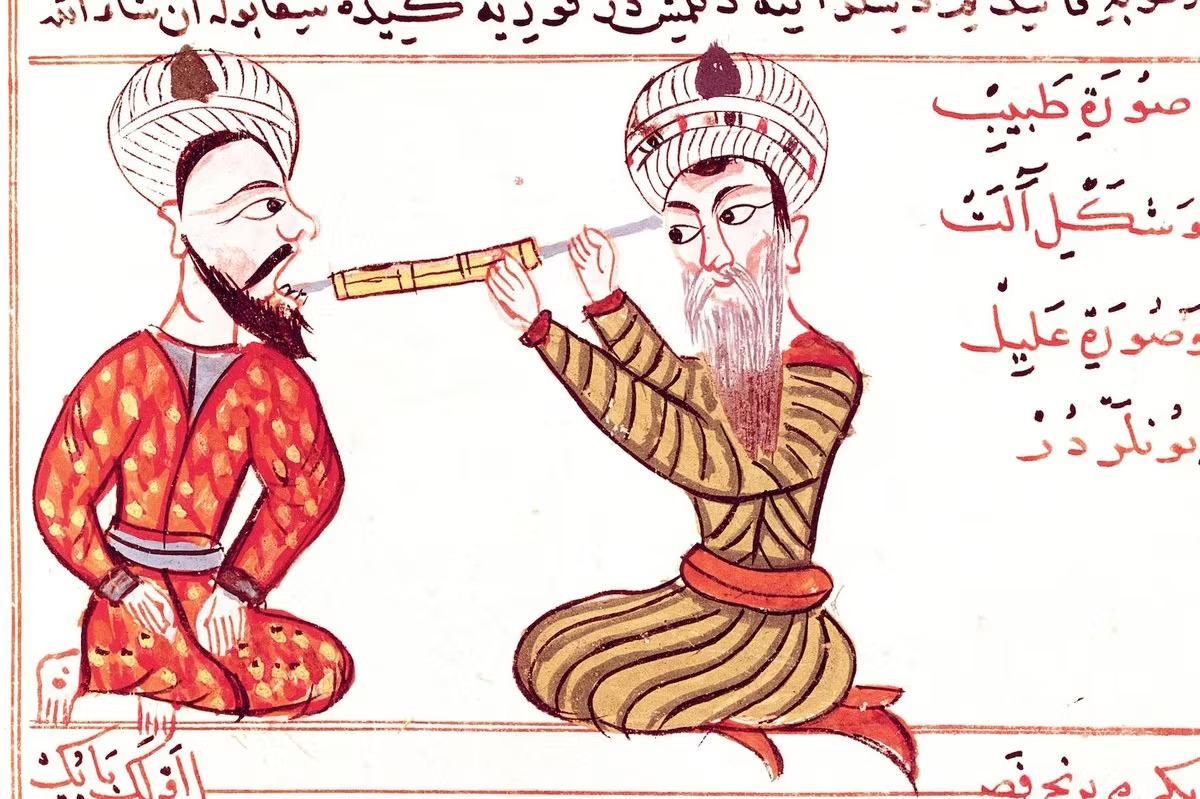

Syringe

Christopher Wren (1632-1723) is often credited as the pioneer of the modern-day syringe.[42] However, as depicted in Figure 3, it was in fact Al-Zahrawi who preceded Wren by over 600 years, utilising a piston system like today’s syringes to deliver medications directly to the target site. It should be noted that Al-Zahrawi’s syringe was mainly used in the treatment of ulcers or urinary pustules.[43]

Figure 3: Al-Zahrawi’s Syringe. Note the piston function and how closely it resembles the modern medicinal syringe.[44]

Surgical Scissors

Most consider and credit Al-Zahrawi as the first to invent and use surgical scissors in surgical procedures.[45] They closely resembled modern surgical scissors with a tempered pivot, equal weight and length of blades, and sharp cutting edges. Al-Zahrawi first describes the use of these scissors in the circumcision of male infants.[46]

Some historians also theorise that Al-Zahrawi’s tonsil guillotine was the very first type of true modern surgical scissors.[47]

Wooden Orthopaedic Bench

Al-Zahrawi invented a specialised bench with built-in mechanised pulleys and ropes to stabilise the patient while also extending or twisting limbs to relocate dislocated joints. This was particularly effective in the realignment of dislocated dorsal vertebrae.[48] This device helped Al-Zahrawi establish the cause of paralysis.

Important Medical and Surgical Procedures of Al-Zahrawi

Lithotripsy

Lithotripsy is a non-invasive, non-surgical procedure that allows large kidney stones to be broken down with the aid of sound waves and, more recently, laser beams to allow them to pass normally through urination. Al-Zahrawi is credited as the founder of lithotripsy. Using catheters and forceps, he was able to effectively reduce kidney stone sizes and allow them to be irrigated. He also pioneered the use of a scalpel in cases of larger kidney stones. He would use the scalpel to make a small incision between the anus and testicles to reach the urethra and crush larger kidney stones directly without the cushion of the skin.[49]

Removal of a Fetus in Ectopic Pregnancy

Al-Zahrawi was credited as the first to use a glass mirror to reflect sunlight to inspect the cervix to better understand and diagnose an irregular or potential ectopic pregnancy.[50] While the Chamberlen family is often attributed with using a cephalotribe (a device to remove a dead fetus from the cervix or vaginal canal in case of an irregular pregnancy), it was in fact first described by Al-Zahrawi in al-Tasrif.

Penile Fracture

Al-Zahrawi is credited as the first physician to diagnose and record cases of penile fracture. He then introduced a cannula to help with the management of the associated pain as well as post-fracture treatments that the patient could complete at home.[51]

Kocher’s Method for Dislocated Shoulder

Modern medical history often credits Emil Kocher (1870) with the Kocher Method (the method was, in fact, named after him). This procedure involves the realignment of the dislocated shoulder by rotating the upper arm in the sagittal plane as far as possible before turning it inwards. While some scholars and historians present evidence that the same method may have been used up to 3,000 years ago (referencing hieroglyphic archives from Ancient Egypt), these hieroglyphics merely present speculative pictures. In fact, it was Al-Zahrawi who, approximately 870 years before Emil Kocher, had documented an almost identical procedure for the replacement of a dislocated shoulder.

Cauterization

Often credited as the father of cauterisation, Al-Zahrawi used more than 50 different types of cauteries (chemicals or devices that aid cauterisation of a bleeding wound to prevent blood loss and infections). Al-Zahrawi was the first among his contemporaries and predecessors to shift away from using gold for cauterisation to using iron. His keen experimental, analytical observation allowed him to gauge and observe the appropriate amount of iron heating, noting the change in colour from its original state to red to white.[52]

Perhaps his biggest contribution to cauterisation involved his discovery of animal gut as a biodegradable and dissolvable material within the human body.[53] In fact, dissolvable suture strings are still made from animal gut—one of the many testimonies to the revolutionary nature of Al-Zahrawi’s discoveries.

Fractures

Al-Zahrawi invented a method to diagnose and identify hairline fractures of the skull and then developed the method to treat the observed fractures using an appropriate surgical saw, specialised forceps, and a specialised chisel.[54] He showed great attention to detail by describing the sensitivity of the dura mater (the toughest, outermost layer of the three membranes that protect the brain and spinal cord) and specifically wrote about the care a physician must take while using a saw or trephine when cutting through the skull.[55]

Al-Zahrawi also invented several methods to diagnose and fix or realign internal nasal fractures.[56]

Al-Zahrawi theorised and constructed various splints to deal with different fractures, ranging from simple to compound fractures. These splint models (including simple, ball, pestle, and coaptation splints) are still used today.[57] He is also credited with adding egg and flour to plaster to help immobilise the affected limb.[58]

Tonsillectomy

Tonsillectomy is the surgical procedure of removing inflamed tonsils (two bulging pieces of tissue at the back of the oral wall that are part of the immune system and help fight off oral and viral infections). While tonsillectomy has been around for thousands of years (with some Hindu records showing crude tonsillectomy as much as 3,000 years ago) and while modern medical historians credit “modern” tonsillectomy—i.e., use of a tongue depressor, hook, scalpel, and guillotine—to 1828 to a physician named Philip Syng Physick,[59] it was Al-Zahrawi who approximately 828 years earlier had successfully performed the first tonsillectomy using surgical tools.[60] He used a tongue depressor (an Al-Zahrawi invention) to keep the tongue down, then inserted a hook (another Al-Zahrawi invention) to stabilise the tonsil before inserting the guillotine (yet another Al-Zahrawi invention and a form of surgical scissors explained in the preceding chapter) to remove the tonsils.[61]

Thyroidectomy

Al-Zahrawi is credited with the first successful thyroidectomy[62] as illustrated in his al-Tasrif. Thyroidectomy is the surgical procedure of removing all or some parts of the thyroid gland. Al-Zahrawi successfully identified thyroid tumours using an aspiration needle (an Al-Zahrawi invention).[63]

Hydrocephalic Identification & Neurologic Treatment

Hydrocephalus is the buildup of fluid within ventricles (brain cavities) within the brain. This buildup of fluid causes pressure on the brain, causing extreme discomfort, pain, and in some cases death. Al-Zahrawi was the first to identify hydrocephalus in infants and paediatrics.[64] He is also credited with developing the first technique to treat infant hydrocephalus. The method involved opening the anterior fontanelle and extracting the fluid (called superficial intracranial fluid) from within, relieving the pressure and often fully curing the infant.[65]

It is through the efforts of Al-Zahrawi that he identified the primary cause of paralysis as fractures of the spinal cord.[66]

Evidence of Laryngotomy & Tracheotomy

In an incident that proved not only the medical genius of Al-Zahrawi but also his empathy and akhlaq, an interesting case was presented to him. As discussed earlier, Al-Zahrawi held no discrimination when treating patients and treated everyone with the same care and precision regardless of social standing. A patient identified as a slave girl who had become disenchanted with her condition struck herself near the anterior midline region of the neck (behind which is the larynx) in an apparent suicide attempt. The gush of blood frightened her, and she rushed to her master, who promptly brought her to Al-Zahrawi’s quarters. Using extreme precision, he was able to sew up the wound and save her life. This small effort, though it may seem minuscule compared to the other achievements of Al-Zahrawi, led him to project in his own writings that tears within the larynx (laryngotomy) and oesophagus (tracheotomy) may be repaired or made to help aid a patient suffering from respiratory problems.[67]

Treatment of Pterygium (Ophthalmology)

Pterygium is a small growth that often starts at the medial end of the eye and begins to extend towards the iris, potentially blocking vision and causing extreme irritation. Al-Zahrawi was the first documented physician to use a scalpel and a needle in the treatment of patients affected with pterygium.[68] The procedure he documented was simple yet effective: the operating physician would insert a small needle under the pterygium growth to raise it and, using a horse-tail hair (Al-Zahrawi theorized that scalpels could potentially be used, but the scalpels at that time were not technologically advanced enough to be below 0.2 mm thickness, which was needed to treat pterygium), the growth would be cut off.[69]

Dental Procedures

While tartar had been identified by Al-Zahrawi’s predecessors, he was the first to credit tartar buildup as the leading cause of gingivitis and other dental diseases.[70] Furthermore, he invented various dental instruments for the removal of tartar buildup.[71]

Modern-day braces are credited to a French dentist named Christophe-François Delabarre; however, it was in fact Al-Zahrawi who first used a gold interchain link wire to fix loose teeth by linking them together.[72]

Al-Zahrawi also postulated prosthetic dentures made of animal bones and teeth to replace teeth in patients who had lost their own, thus paving the way for dentures several centuries later.[73]

Procedures Pertaining to Bleeding Control, Wound Healing & Pain Management

Considered a pioneer in controlling bleeding and managing patient pain, Al-Zahrawi established several practices which are still in use today, including: using cotton to control bleeding, plaster for fractures, and using adhesive bandages (using a concoction that he invented).[74]

Al-Zahrawi was the first to develop an anaesthetic sponge (rather than gaseous or liquid anaesthetic), which is considered to be the main precursor of modern anaesthesia.[75]

Cosmetic Procedures

Often credited as the first cosmetic surgeon, Al-Zahrawi dedicated Chapter 19 in al-Tasrif to cosmetic procedures and named the chapter “Medicine of Beauty.”[76] Within this chapter, he went into detail on how to whiten teeth,[77] removal of warts using an iron tube and caustic metal,[78] as well as invented various hair-removal sticks. Perhaps most interestingly, he fathered modern-day deodorants by describing incense and perfumes which he postulated could be rolled and then pressed into sticks.[79]

Conclusion

There is no doubt that Al-Zahrawi was a towering figure and a man who reached the pinnacle of science and medicine. Much of the surgical landscape today was greatly influenced by the work of Al-Zahrawi, and without him, modern medicine may have looked very different. The intellectual landscape that brought forth the likes of Al-Zahrawi, and perhaps more importantly, that allowed Al-Zahrawi and his contemporaries to cultivate their scientific and medical curiosity, represents a remarkable achievement in human history.

Al-Andalus represents a “Golden Age of Islam.” It offers a world where religious spaces and secular spaces can not only coexist but thrive together. It demonstrates the compatibility of Islam with scientific advancement. Al-Andalusian Islam represented a world not too different from our own. It allowed for the cultivation of philosophy, Islam, and science to amalgamate in a way that enabled thinkers to develop solutions to the problems they faced. Muslims today need to embrace the same approach. The problems facing the ummah today are vastly different from those facing the ummah a few decades ago. The scholars today must rise up and respond to challenges facing Islam, but they can only do so if they understand Western, modern, and contemporary culture as much as mainstream traditional Islamic culture. Perhaps by studying the personalities of Andalusian Islam and how they rose above the challenges they faced to preserve both their personal deen and represent Islam on a global scale, we may be able to rise from the age-old limitations of narrow thinking and once again be pioneers in theology, philosophy, science, astronomy, mathematics, politics, and governance.

At the conclusion of this research, one is compelled to conclude that Andalusian intellectual ilm was an ilm that belongs in a category all its own. It was unique, different, but at the same time comprehensive and unifying. Al-Andalus represents a lesson in growth, scientific discovery, collaboration, and exponential increase in scientific and technological advancements. Al-Andalus gives us a glimmer of hope that Islam is indeed compatible with both Western theology and modern science.

[1]Richard Covington, “Rediscovering Arabic Science,” ed. Robert Arndt, Saudi Aramco World 58, no. 3 (2007): 2–16.

[2]J. Bradford De Long and Andrei Shleifer, “Princes and Merchants: European City Growth before the Industrial Revolution,” The Journal of Law and Economics 36, no. 2 (October 1993): 678.

[3]J. Vernet, “Ibn Wāfid, Abū Al-Mutarrif ‘Abd Alrahman,” in Complete Dictionary of Scientific Biography (Encyclopedia.com, 2008).

[4]Ṣāʻid ibn Aḥmad Andalusī, Semaʻan I. Salem, and Alok Kumar, Science in the medieval world: book of the Categories of nations (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1991), 100.

[5]Ibid.

[6]S. Kaf al-Ghazal, “Al-Zahrawi (Albucasis) the great Andalusian surgeon,” in Selected Gleanings from the History of Islamic Medicine, ed. M. El-Gomati, M. Abattouy, and S. Ayduz (Foundation for Science Technol & Civilization, 2007).

[7]Sami Khalaf Hamarneh and Glenn Allen Sonnedecker, A Pharmaceutical View of Abulcasis Al-Zahrāwī in Moorish Spain: With Special Reference to the “Adhān” (Leiden: Brill Archive, 1963), 15.

[8]De Long and Shleifer, “Princes and Merchants,” 678.

[9]Kaf al-Ghazal, “Al-Zahrawi (Albucasis).”

[10]Ibid.

[11]Rachid El Hour, “Jadhwat al-muqtabis fī ta’rīkh ʿulamā’ al-Andalus,” in Christian Muslim Relations Online I, ed. D. Thomas (Brill, 2010).

[12]I. A. Nabri, “El Zahrawi (936-1013 AD), the father of operative surgery,” Annals of the Royal College of Surgeons of England 65, no. 2 (March 1983): 132–134.

[13]Ibid.

[14]M. Ignjatovic, “Overview of the history of thyroid surgery,” Acta Chirurgica Iugoslavica 50 (2003): 9–36.

[15]Madainproject.com, “Kitab al-Tasrif,” 2022, accessed April 6, 2025, https://madainproject.com/kitab_al_tasrif.

[16]Alfred Aschoff et al., “The scientific history of hydrocephalus and its treatment,” Neurosurgical Review 22 (1999): 67-93.

[17]Max E. Valentinuzzi, “Could Al-Zahrawi Be Considered a Biomedical Engineer?” IEEE Pulse, March 4, 2016.

[18]Nabri, “El Zahrawi,” 132–134.

[19]Rachid El Hour, “Jadhwat al-muqtabis fī ta’rīkh ʿulamā’ al-Andalus,” in Christian Muslim Relations Online I, ed. D. Thomas (Brill, 2010).

[20]S. Kaf al-Ghazal, “Al-Zahrawi (Albucasis) the great Andalusian surgeon,” in Selected Gleanings from the History of Islamic Medicine, ed. M. El-Gomati, M. Abattouy, and S. Ayduz (Foundation for Science Technol & Civilization, 2007).

[21]Ibid.

[22]Ibid.

[23]I. A. Nabri, “El Zahrawi (936-1013 AD), the father of operative surgery,” Annals of the Royal College of Surgeons of England 65, no. 2 (March 1983): 132–134.

[24]Ibid.

[25]Madainproject.com, “Kitab al-Tasrif,” 2022, accessed April 6, 2025, https://madainproject.com/kitab_al_tasrif.

[26]Sami Khalaf Hamarneh and Glenn Allen Sonnedecker, A Pharmaceutical View of Abulcasis Al-Zahrāwī in Moorish Spain: With Special Reference to the “Adhān” (Leiden: Brill Archive, 1963), 40.

[27]Nabri, “El Zahrawi,” 132–134.

[28]Ibid.

[29]Madainproject.com, “Kitab al-Tasrif.”

[30]Nabri, “El Zahrawi,” 132–134.

[31]Madainproject.com, “Kitab al-Tasrif.”

[32]Ibid.

[33]Ibid.

[34]Hamarneh and Sonnedecker, A Pharmaceutical View of Abulcasis Al-Zahrāwī, 43.

[35]Nabri, “El Zahrawi,” 132–134.

[36]Ibid.

[37]Nabri, “El Zahrawi,” 132–134.

[38]Hamarneh and Sonnedecker, A Pharmaceutical View of Abulcasis Al-Zahrāwī, 39.

[39]Nabri, “El Zahrawi,” 132–134.

[40]Ibid.

[41]Ibid.

[42]Hamarneh and Sonnedecker, A Pharmaceutical View of Abulcasis Al-Zahrāwī, 42.

[43]Nabri, “El Zahrawi,” 132–134.

[44]Hamarneh and Sonnedecker, A Pharmaceutical View of Abulcasis Al-Zahrāwī, 39.

[45]Nabri, “El Zahrawi,” 132–134.

[46]Ibid.

[47]Nabri, “El Zahrawi,” 132–134.

[48]Hamarneh and Sonnedecker, A Pharmaceutical View of Abulcasis Al-Zahrāwī, 45.

[49]Hamarneh and Sonnedecker, A Pharmaceutical View of Abulcasis Al-Zahrāwī, 41.

[50]Ibid., 48.

[51]Nabri, “El Zahrawi,” 132–134.

[52]Ibid.

[53]Ibid.

[54]Ibid.

[55]Ibid.

[56]Nabri, “El Zahrawi,” 132–134.

[57]Ibid.

[58]Ibid.

[59]Nabri, “El Zahrawi,” 132–134.

[60]Ibid.

[61]Ibid.

[62]M. Ignjatovic, “Overview of the history of thyroid surgery,” Acta Chirurgica Iugoslavica 50 (2003): 9–36.

[63]Nabri, “El Zahrawi,” 132–134.

[64]Alfred Aschoff et al., “The scientific history of hydrocephalus and its treatment,” Neurosurgical Review 22 (1999): 67-93.

[65]Ibid.

[66]Hamarneh and Sonnedecker, A Pharmaceutical View of Abulcasis Al-Zahrāwī, 49.

[67]Ibid., 34.

[68]Nabri, “El Zahrawi,” 132–134.

[69]Ibid.

[70]Ibid.

[71]Ibid.

[72]Ibid.

[73]Ibid.

[74]Ibid.

[75]Ibid.

[76]Hamarneh and Sonnedecker, A Pharmaceutical View of Abulcasis Al-Zahrāwī, 32.

[77]Ibid.

[78]Ibid., 33.

[79]Ibid., 32.